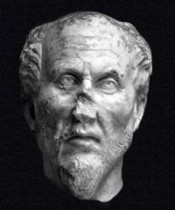

plotinus

Plotinus (Greek: Πλωτῖνος) (ca. CE 204–270) was a major philosopher of the ancient world who is widely considered the founder of Neoplatonism (along with his teacher Ammonius Saccas). Neoplatonism was an influential philosophy in Late Antiquity. Much of our biographical information about Plotinus comes from Porphyry's preface to his edition of Plotinus' Enneads. His metaphysical writings have inspired centuries of Pagan, Christian, Jewish, Islamic and Gnostic metaphysicians and mystics. Porphyry reported that Plotinus was 66 years old when he died in 270, the second year of the reign of the emperor Claudius II, thus giving us the year of his teacher's birth as around 205. Eunapius reported that Plotinus was born in the Deltaic Lycopolis (Latin: Lyco) in Egypt, which has led to speculations that he may have been a native Egyptian of Roman,[1] Greek,[2] or Hellenized Egyptian[3] descent. Plotinus had an inherent distrust of materiality (an attitude common to Platonism), holding to the view that phenomena were a poor image or mimicry (mimesis) of something "higher and intelligible" [VI.I] which was the "truer part of genuine Being". This distrust extended to the body, including his own; it is reported by Porphyry that at one point he refused to have his portrait painted, presumably for much the same reasons of dislike. Likewise Plotinus never discussed his ancestry, childhood, or his place or date of birth. From all accounts his personal and social life exhibited the highest moral and spiritual standards. Plotinus took up the study of philosophy at the age of twenty-seven, around the year 232, and travelled to Alexandria to study. There Plotinus was dissatisfied with every teacher he encountered until an acquaintance suggested he listen to the ideas of Ammonius Saccas. Upon hearing Ammonius lecture, he declared to his friend, "this was the man I was looking for," and began to study intently under his new instructor. Besides Ammonius, Plotinus was also influenced by the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias, Numenius, and various Stoics. After spending the next eleven years in Alexandria, he then decided to investigate the philosophical teachings of the Persian philosophers and the Indian philosophers around the age of 38.[4] In the pursuit of this endeavor he left Alexandria and joined the army of Gordian III as it marched on Persia. However, the campaign was a failure, and on Gordian's eventual death Plotinus found himself abandoned in a hostile land, and only with difficulty found his way back to safety in Antioch. At the age of forty, during the reign of Philip the Arab, he came to Rome, where he stayed for most of the remainder of his life. There he attracted a number of students. His innermost circle included Porphyry, Amelius Gentilianus of Tuscany, the Senator Castricius Firmus, and Eustochius of Alexandria, a doctor who devoted himself to learning from Plotinus and attended to him until his death. Other students included: Zethos, an Arab by ancestry who died before Plotinus, leaving him a legacy and some land; Zoticus, a critic and poet; Paulinus, a doctor of Scythopolis; and Serapion from Alexandria. He had students amongst the Roman Senate beside Castricius, such as Marcellus Orontius, Sabinillus, and Rogantianus. Women were also numbered amongst his students, including Gemina, in whose house he lived during his residence in Rome, and her daughter, also Gemina; and Amphiclea, the wife of Ariston the son of Iamblichus.[5] Finally, Plotinus was a correspondent of the philosopher Cassius Longinus. While in Rome Plotinus also gained the respect of the Emperor Gallienus and his wife Salonina. At one point Plotinus attempted to interest Gallienus in rebuilding an abandoned settlement in Campania, known as the 'City of Philosophers', where the inhabitants would live under the constitution set out in Plato's Laws. An Imperial subsidy was never granted, for reasons unknown to Porphyry, who reports the incident. Porphyry subsequently went to live in Sicily, where word reached him that his former teacher had died. The philosopher spent his final days in seclusion on an estate in Campania which his friend Zethos had bequeathed him. According to the account of Eustochius, who attended him at the end, Plotinus' final words were: "Strive to give back the Divine in yourselves to the Divine in the All." Eustochius records that a snake crept under the bed where Plotinus lay, and slipped away through a hole in the wall; at the same moment the philosopher died. Plotinus wrote the essays that became the Enneads over a period of several years from ca. 253 until a few months before his death seventeen years later. Porphyry makes note that the Enneads, before being compiled and arranged by himself, were merely the enormous collection of notes and essays which Plotinus used in his lectures and debates, rather than a formal book. Plotinus was unable to revise his own work due to his poor eyesight, yet his writings required extensive editing, according to Porphyry: his master's handwriting was atrocious, he did not properly separate his words, and he cared little for niceties of spelling. Plotinus intensely disliked the editorial process, and turned the task to Porphyry, who not only polished them but put them into the arrangement we now have. Plotinus taught that there is a supreme, totally transcendent "One", containing no division, multiplicity or distinction; likewise it is beyond all categories of being and non-being. The concept of "being" is derived by us from the objects of human experience called the dyad, and is an attribute of such objects, but the infinite, transcendent One is beyond all such objects, and therefore is beyond the concepts that we derive from them. The One "cannot be any existing thing", and cannot be merely the sum of all such things (compare the Stoic doctrine of disbelief in non-material existence), but "is prior to all existents". Thus, no attributes can be assigned to the One. We can only identify it with the Good and the principle of Beauty. [I.6.9] For example, thought cannot be attributed to the One because thought implies distinction between a thinker and an object of thought (again dyad). Even the self-contemplating intelligence (the noesis of the nous) must contain duality. "Once you have uttered 'The Good,' add no further thought: by any addition, and in proportion to that addition, you introduce a deficiency." [III.8.11] Plotinus denies sentience, self-awareness or any other action (ergon) to the One [V.6.6]. Rather, if we insist on describing it further, we must call the One a sheer Dynamis or potentiality without which nothing could exist. [III.8.10] As Plotinus explains in both places and elsewhere [e.g. V.6.3], it is impossible for the One to be Being or a self-aware Creator God. At [V.6.4], Plotinus compared the One to "light", the Divine Nous (first will towards Good) to the "Sun", and lastly the Soul to the "Moon" whose light is merely a "derivative conglomeration of light from the 'Sun'". The first light could exist without any celestial body. The One, being beyond all attributes including being and non-being, is the source of the world—but not through any act of creation, willful or otherwise, since activity cannot be ascribed to the unchangeable, immutable One. Plotinus argues instead that the multiple cannot exist without the simple. The "less perfect" must, of necessity, "emanate", or issue forth, from the "perfect" or "more perfect". Thus, all of "creation" emanates from the One in succeeding stages of lesser and lesser perfection. These stages are not temporally isolated, but occur throughout time as a constant process. Plotinus here resolves the issues between Plato's ontology and Aristotle's Actus et potentia. The issue being that Aristotle, through resolving Parmenides' Third Man argument against Plato's forms and ontology created a second philosophical school of thought. Plotinus here then reconciles the "Good over the Demiurge" from Plato's Timaeus with Aristotle's static "unmoved mover" of Actus et potentia. Plotinus does this by making the potential or force (dunamis) the Monad or One and making the demiurge or dyad, the action or energy component in philosophical cognitive ontology. Later Neoplatonic philosophers, especially Iamblichus, added hundreds of intermediate beings as emanations between the One and humanity; but Plotinus' system was much simpler in comparison. Plotinus offers an alternative to the orthodox Christian notion of creation ex nihilo (out of nothing), which attributes to God the deliberation of mind and action of a will, although Plotinus never mentions Christianity in any of his works. Emanation ex deo (out of God), confirms the absolute transcendence of the One, making the unfolding of the cosmos purely a consequence of its existence; the One is in no way affected or diminished by these emanations. Plotinus uses the analogy of the Sun which emanates light indiscriminately without thereby diminishing itself, or reflection in a mirror which in no way diminishes or otherwise alters the object being reflected. The first emanation is nous (thought or the divine mind, logos or order, reason), identified metaphorically with the demiurge in Plato's Timaeus. It is the first will towards Good. From nous proceeds the world soul, which Plotinus subdivides into upper and lower, identifying the lower aspect of Soul with nature. From the world soul proceeds individual human souls, and finally, matter, at the lowest level of being and thus the least perfected level of the cosmos. Despite this relatively pedestrian assessment of the material world, Plotinus asserted the ultimately divine nature of material creation since it ultimately derives from the One, through the mediums of nous and the world soul. It is by the Good or through beauty that we recognize the One, in material things and then in the Forms.[6] The essentially devotional nature of Plotinus' philosophy may be further illustrated by his concept of attaining ecstatic union with the One (henosis see Iamblichus). Porphyry relates that Plotinus attained such a union four times during the years he knew him. This may be related to enlightenment, liberation, and other concepts of mystical union common to many Eastern and Western traditions. Some have compared Plotinus' teachings to the Hindu school of Advaita Vedanta (advaita "not two", or "non-dual"),[7].

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like plotinus try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like plotinus try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!