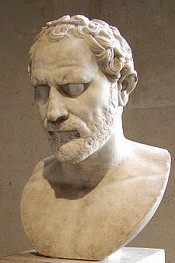

demosthenes

Demosthenes (384–322 BC, Greek: Δημοσθένης, Dēmosthénēs) was a prominent Greek statesman and orator of ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide an insight into the politics and culture of ancient Greece during the 4th century BC. Demosthenes learned rhetoric by studying the speeches of previous great orators. He delivered his first judicial speeches at the age of 20, in which he argued effectively to gain from his guardians what was left of his inheritance. For a time, Demosthenes made his living as a professional speech-writer (logographer) and a lawyer, writing speeches for use in private legal suits. Demosthenes grew interested in politics during his time as a logographer, and in 354 BC he gave his first public political speeches. He went on to devote his most productive years to opposing Macedon's expansion. He idealized his city and strove throughout his life to restore Athens' supremacy and motivate his compatriots against Philip II of Macedon. He sought to preserve his city's freedom and to establish an alliance against Macedon, in an unsuccessful attempt to impede Philip's plans to expand his influence southwards by conquering all the Greek states. After Philip's death, Demosthenes played a leading part in his city's uprising against the new King of Macedon, Alexander the Great. However, his efforts failed and the revolt was met with a harsh Macedonian reaction. To prevent a similar revolt against his own rule, Alexander's successor in this region, Antipater, sent his men to track Demosthenes down. Demosthenes took his own life, in order to avoid being arrested by Archias, Antipater's confidant. The Alexandrian Canon compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace recognized Demosthenes as one of the ten greatest Attic orators and logographers. According to Longinus, Demosthenes "perfected to the utmost the tone of lofty speech, living passions, copiousness, readiness, speed".[1] Cicero acclaimed him as "the perfect orator" who lacked nothing, and Quintilian extolled him as lex orandi ("the standard of oratory") and that inter omnes unus excellat ("he stands alone among all the orators").[2][3] Demosthenes was born in 384 BC, during the last year of the 98th Olympiad or the first year of the 99th Olympiad.[4] His father—also named Demosthenes—who belonged to the local tribe, Pandionis, and lived in the deme of Paeania[5] in the Athenian countryside, was a wealthy sword-maker.[6] Aeschines, Demosthenes' greatest political rival, maintained that his mother Kleoboule was a Scythian by blood[7]—an allegation disputed by some modern scholars.[a] Demosthenes was orphaned at the age of seven. Although his father provided well for him, his legal guardians, Aphobus, Demophon and Therippides, mishandled his inheritance.[8] As soon as Demosthenes came of age in 366 BC, he demanded they render an account of their management. According to Demosthenes, the account revealed the misappropriation of his property. Although his father left an estate of nearly fourteen talents,[9] (very roughly 11,700 troy ounces in silver or 150,000 current United States dollars)[10] Demosthenes asserted his guardians had left nothing "except the house, and fourteen slaves and thirty silver minae" (30 minae = ½ talent).[11] At the age of 20, Demosthenes sued his trustees in order to recover his patrimony and delivered five orations — three Against Aphobus during 363 BC and 362 BC and two Against Ontenor during 362 and 361 BC. The courts fixed Demosthenes' damages at ten talents.[12] When all the trials came to an end,[b] he only succeeded in retrieving a portion of his inheritance.[10] Between his coming of age in 366 BC and the trials that took place in 364 BC, Demosthenes and his guardians negotiated acrimoniously but were unable to reach an agreement, for neither side was willing to make concessions.[10] At the same time, Demosthenes prepared himself for the trials and improved his oratory skill. As an adolescent, his curiosity had been noticed by the orator Callistratus, who was then at the height of his reputation, having just won a case of considerable importance.[13] According to Friedrich Nietzsche, a German philologist and philosopher, and Constantine Paparregopoulus, a major Greek historian, Demosthenes was a student of Isocrates;[14][15] according to Cicero, Quintillian and the Roman biographer Hermippus, he was a student of Plato.[13] Lucian, a Roman-Syrian rhetorician and satirist, lists the philosophers Aristotle, Theophrastus and Xenocrates among his teachers.[16] These claims are nowadays disputed.[c] According to Plutarch, Demosthenes employed Isaeus as his master in Rhetoric, even though Isocrates was then teaching this subject, either because he could not pay Isocrates the prescribed fee or because Demosthenes believed Isaeus' style better suited a vigorous and astute orator such as himself .[13] Curtius, a German archaeologist and historian, likened the relation between Isaeus and Demosthenes to "an intellectual armed alliance".[17] It has also been said that Demosthenes paid Isaeus 10,000 drachmae (somewhat over 1.5 talents) on the condition that Isaeus should withdraw from a school of Rhetoric which he had opened, and should devote himself wholly to Demosthenes, his new pupil.[17] Another version credits Isaeus with having taught Demosthenes without charge.[18] According to Sir Richard C. Jebb, a British classical scholar, "the intercourse between Isaeus and Demosthenes as teacher and learner can scarcely have been either very intimate or of very long duration".[17] Konstantinos Tsatsos, a Greek professor and academician, believes that Isaeus helped Demosthenes edit his initial judicial orations against his guardians.[19] Demosthenes is also said to have admired the historian Thucydides. In the Illiterate Book-Fancier, Lucian mentions eight beautiful copies of Thucydides made by Demosthenes, all in Demosthenes' own handwriting.[20] These references hint at his respect for a historian he must have assiduously studied.[21] According to Pseudo-Plutarch, Demosthenes was married once. The only information about his wife, whose name is unknown, is that she was the daughter of Heliodorus, a prominent citizen.[22] Demosthenes also had a daughter, "the only one who ever called him father", according to Aeschines' in a trenchant remark.[23] His daughter died young and unmarried a few days before Philip's death.[23] In his speeches, Aeschines often uses the pederastic relations of Demosthenes to attack him. The essence of these attacks was not that Demosthenes had relations with boys, but that he had been an inadequate pederast, one whose attentions did not benefit the boys, as would have been expected, but harmed them instead. In the case of Aristion, a youth from Plataea who lived for a long time in Demosthenes' house, Aeschines mocked him for lack of sexual restraint and possibly effeminate behavior: "Allegations about what [Aristion] was undergoing there, or doing what, vary, and it would be most unseemly for me to talk about it."[24] Another relationship which Aeschines brings up is that with Cnosion. His allegation, in this case, was also of a sexual nature. This time, however, he blamed Demosthenes for involving his wife by putting her in bed with the youth so as to get children by him.[25] Athenaeus, however, presents matters in a different light, claiming that his wife bedded the boy in a fit of jealousy.[26] Aeschines often asserted that Demosthenes made money out of young rich men. He claimed that he deluded Aristarchus, the son of Moschus, with the pretence that he could make him a great orator.[27] Apparently, while still under Demosthenes' tutelage, Aristarchus killed and mutilated a certain Nicodemus of Aphidna, gouging out his eyes and tongue. Aeschines accused Demosthenes of complicity in the murder, pointing out that Nicodemus had once pressed a lawsuit accusing Demosthenes of desertion. He also accused Demosthenes of having been such a bad erastes to Aristarchus so as not even to deserve the name. His crime, according to Aeschines, was to have betrayed his eromenos by pillaging his estate, allegedly pretending to be in love with the youth so as to get his hands on the boy's inheritance. This he is said to have squandered, having taken three talents upon Aristarchus' fleeing into exile so as to avoid a trial. Thus, in payment for the trust that Aristarchus and his family put in him, "You entered a happy home [...] you ruined it."[28] Nevertheless, the story of Demosthenes' relations with Aristarchus is still regarded as more than doubtful, and no other pupil of Demosthenes is known by name.[27] To make his living, Demosthenes became a professional litigant and logographer, writing speeches for use in private legal suits. He was so successful that he soon acquired wealthy and powerful clients. The Athenian logographer could remain anonymous, allowing him to serve personal interests, even if it prejudiced the client. Aeschines accused Demosthenes of unethically disclosing his clients' arguments to their opponents.[29] He queried of Demosthenes: "And the born traitor—how shall we recognize him? Will he not imitate you, Demosthenes, in his treatment of those whom chance throws in his way and who have trusted him? Will he not take pay for writing speeches for them to deliver in the courts, and then reveal the contents of these speeches to their opponents?"[30] As an example, Aeschines accused Demosthenes of writing a speech for Phormion, a wealthy banker, and then communicating it to Apollodorus, who was bringing a capital charge against Phormion.[30] Plutarch supported this accusation, stating that Demosthenes "was thought to have acted dishonorably".[31] Even before he turned 21-years-old in 363 BC, Demosthenes had already demonstrated an interest in politics.[10] In 363, 359, and 357 BC, he assumed the office of the trierarch, being responsible for the outfitting and maintenance of a trireme.[32] In 348 BC, he became a choregos, paying the expenses of a theatrical production.[33] Although Demosthenes said he never pleaded a single private case,[34] it remains unclear when and if Demosthenes abandoned the profitable but not so prestigious profession of logography.[d] According to Plutarch, when Demosthenes first addressed himself to the people, he was derided for his strange and uncouth style, "which was cumbered with long sentences and tortured with formal arguments to a most harsh and disagreeable excess".[35]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like demosthenes try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like demosthenes try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!