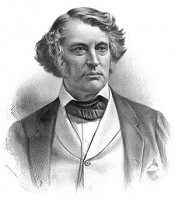

Sumner Charles

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811 – March 11, 1874) was an American politician and statesman from Massachusetts. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction, and the counterpart to Thaddeus Stevens in the United States House of Representatives. He jumped from party to party, gaining fame as a Republican. One of the most learned statesmen of the era, he specialized in foreign affairs, working closely with Abraham Lincoln. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the scheme of slave owners to take control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. His severe beating in 1856 by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks on the floor of the United States Senate helped escalate the tensions that led to war. After years of therapy Sumner returned to the Senate to help lead the Civil War. Sumner was a leading proponent of abolishing slavery to weaken the Confederacy. Although he kept on good terms with Abraham Lincoln, he was a leader of the hard-line Radical Republicans. As a Radical Republican leader in the Senate during Reconstruction, 1865-1871, Sumner fought hard to provide equal civil and voting rights for the freedmen (on the grounds that "consent of the governed" was a basic principle of American republicanism), and to block ex-Confederates from power so they would not reverse the victory in the Civil War. Sumner, teaming with House leader Thaddeus Stevens, defeated Andrew Johnson, and imposed Radical views on the South. In 1871, however, he broke with President Ulysses Grant; Grant's Senate supporters then took away Sumner's power base, his committee chairmanship. Sumner, concluding that Grant's corruption and the success of Reconstruction policies called for new national leadership, supported the Liberal Republicans candidate Horace Greeley in 1872 and lost his power inside the Republican party. Scholars consider Sumner and Stevens to be among America's foremost champions of black rights before and after the Civil War; one historian says he was "perhaps the least racist man in America in his day."[1] Sumner's friend Senator Carl Schurz praised Sumner's integrity, his "moral courage," the "sincerity of his convictions," and the "disinterestedness of his motives." However, Sumner's Pulitzer-prize-winning biographer, David Donald, presents Sumner as an insufferably arrogant moralist; an egoist bloated with pride; pontifical and Olympian, and unable to distinguish between large issues and small ones. What's more, concludes Donald, Sumner was a coward who avoided confrontations with his many enemies, whom he routinely insulted in prepared speeches.[2] Biographer David Donald has probed Sumner's psychology:[3] Sumner was the scholar in politics. He could never be induced to suit his action to the political expediency of the moment. "The slave of principles, I call no party master," was the proud avowal with which he began his service in the Senate. For the tasks of Reconstruction he showed little aptitude. He was less a builder than a prophet. His was the first clear program proposed in Congress for the reform of the civil service. It was his dauntless courage in denouncing compromise, in demanding the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, and in insisting upon emancipation, that made him the chief initiating force in the struggle that put an end to slavery. Sumner was born in Boston on Irving Street on January 6, 1811. He was the son of a progressive Harvard-educated lawyer, Charles Pinckney Sumner, an abolitionist and early proponent of racially integrated schools, who shocked 19th century Boston by standing in opposition to anti-miscegenation laws.[4] Though his father had managed to obtain a Harvard education, he had been born in poverty.[5] Sumner's mother shared a similar background, having worked as a seamstress prior to her marriage.[5] Sumner's parents were described as exceedingly formal and undemonstrative.[5] His father's legal practice was a failure, and all throughout Sumner's childhood his family teetered on the edge of the middle class, avoiding poverty only as a result of his mother's Spartan budget.[5] Sumner attended the Boston Latin School, where he counted Robert Charles Winthrop, James Freeman Clarke, Samuel Francis Smith, and Wendell Phillips, among his closest friends.[4] He graduated in 1830 from Harvard College (where he lived in Hollis Hall), and in 1834 from Harvard Law School where he studied jurisprudence and became a protege of Joseph Story. At Harvard, he was a member of the Porcellian Club. In 1834, Sumner was admitted to the bar, entering private practice in Boston, where he partnered with George Stillman Hillard. A visit to Washington filled him with loathing for politics as a career, and he returned to Boston resolved to devote himself to the practice of law. He contributed to the quarterly American Jurist and edited Story's court decisions as well as some law texts. From 1836 to 1837, Sumner lectured at Harvard Law School. He is an honorary member of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity. From 1837 to 1840, Sumner traveled extensively in Europe. There he became fluent in French, Spanish, German and Italian, with a command of languages equaled by no American then in public life. He met with many of the leading statesmen in Europe, and secured a deep insight into civil law and government. Sumner visited England in 1838 where his knowledge of literature, history, and law made him popular with leaders of thought. Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux declared that he "had never met with any man of Sumner's age of such extensive legal knowledge and natural legal intellect." Not until many years after Sumner's death was any other American received so intimately into British intellectual circles. In 1840, at the age of 29, Sumner returned to Boston to practice law but devoted more time to lecturing at Harvard Law School, to editing court reports, and to contributing to law journals, especially on historical and biographical themes. A turning point in Sumner's life came when he delivered an Independence Day oration on "The True Grandeur of Nations," in Boston in 1845. He spoke against war, and made an impassioned appeal for freedom and peace. He became a sought-after orator for formal occasions. His lofty themes and stately eloquence made a profound impression; his platform presence was imposing (he stood six feet and four inches tall, with a massive frame). His voice was clear and of great power; his gestures unconventional and individual, but vigorous and impressive. His literary style was florid, with much detail, allusion, and quotation, often from the Bible as well as ancient Greece and Rome. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote that he delivered speeches "like a cannoneer ramming down cartridges," while Sumner himself said that "you might as well look for a joke in the Book of Revelation." Sumner cooperated effectively with Horace Mann to improve the system of public education in Massachusetts. He advocated prison reform and opposed the Mexican-American War. He viewed the war as a war of aggression but was primarily concerned that captured territories would expand slavery westward. In 1847, the vigor with which Sumner denounced a Boston congressman's vote in favor of the declaration of war against Mexico made him a leader of the "conscience Whigs," but he declined to accept their nomination for the House of Representatives. Sumner took an active part in the organizing of the Free Soil Party, in opposition to the Whigs' nomination of a slave-holding southerner for the presidency. In 1848, he was defeated as a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives. He became senator as a Democrat in 1850, but later became a Republican. In 1851, control of the Massachusetts General Court was secured by the Democrats in coalition with the Free Soilers. However, the legislature deadlocked on who should succeed Daniel Webster in the U.S. Senate. After filling the state positions with Democrats, the Democrats refused to vote for Sumner (the Free Soilers' choice) and urged the selection of a less radical candidate. An impasse of more than three months ensued, which finally resulted in the election of Sumner by a single vote on April 24. Sumner took his seat in the United States Senate in late 1851, as a Democrat. For the first few sessions, the abolitionist-democratic and reformist Sumner did not push for any of his controversial causes, but observed the workings of the Senate. On August 26, 1852, Sumner, in spite of strenuous efforts to prevent it, delivered his first major speech. Entitled "Freedom National; Slavery Sectional" (a popular abolitionist motto), Sumner attacked the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and called for its repeal. The conventions of both the great parties had just affirmed the finality of every provision of the Compromise of 1850. Reckless of political expediency, Sumner moved that the Fugitive Slave Act be forthwith repealed; and for more than three hours he denounced it as a violation of the Constitution, an affront to the public conscience, and an offense against divine law. The speech provoked a storm of anger in the South, but the North was heartened to find at last a leader whose courage matched his conscience. In 1856, during the Bleeding Kansas crisis when "border ruffians" approached Lawrence, Kansas, Sumner denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act in the "Crime against Kansas" speech on May 19 and May 20, two days before the sack of Lawrence. Sumner attacked the authors of the act, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, comparing Butler to Don Quixote and Douglas to Sancho Panza. Sumner said Douglas (who was present in the chamber) was a "noisome, squat, and nameless animal ... not a proper model for an American senator." He also portrayed Butler as having taken "a mistress who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean, the harlot, Slavery." Sumner's three-hour oration later became particularly personally insulting as he mocked the 59-year-old Butler's manner of speech and physical mannerisms, both of which were impaired by a stroke that Butler had suffered earlier.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Duel Between France and Germany

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874) was an American politician and statesman. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction along with Thaddeus Stevens. He jumped from party to party, gaining fame as a Republican. One of the most learned statesmen of the era, he specialized in foreign affairs, working closely with Abraham Lincoln. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. Sumner was a leading proponent of abolishing slavery to weaken the Confederacy. The annexation of Texas - a new slave-holding state - in 1845 pushed Sumner into taking an active role in the anti-slavery movement. He helped organize an alliance between Democrats and the newly created Free-Soil Party in Massachusetts in 1849. His works include The Duel Between France and Germany (1870), Works (1870) and The Best Portraits in Engraving (1875).

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Best Portraits in Engraving

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874) was an American politician and statesman. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction along with Thaddeus Stevens. He jumped from party to party, gaining fame as a Republican. One of the most learned statesmen of the era, he specialized in foreign affairs, working closely with Abraham Lincoln. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. Sumner was a leading proponent of abolishing slavery to weaken the Confederacy. The annexation of Texas - a new slave-holding state - in 1845 pushed Sumner into taking an active role in the anti-slavery movement. He helped organize an alliance between Democrats and the newly created Free-Soil Party in Massachusetts in 1849. His works include The Duel Between France and Germany (1870), Works (1870) and The Best Portraits in Engraving (1875).

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Duel Between France and Germany

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874) was an American politician and statesman. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction along with Thaddeus Stevens. He jumped from party to party, gaining fame as a Republican. One of the most learned statesmen of the era, he specialized in foreign affairs, working closely with Abraham Lincoln. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. Sumner was a leading proponent of abolishing slavery to weaken the Confederacy. The annexation of Texas - a new slave-holding state - in 1845 pushed Sumner into taking an active role in the anti-slavery movement. He helped organize an alliance between Democrats and the newly created Free-Soil Party in Massachusetts in 1849. His works include The Duel Between France and Germany (1870), Works (1870) and The Best Portraits in Engraving (1875).

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Best Portraits in Engraving

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874) was an American politician and statesman. An academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the antislavery forces in Massachusetts and a leader of the Radical Republicans in the United States Senate during the American Civil War and Reconstruction along with Thaddeus Stevens. He jumped from party to party, gaining fame as a Republican. One of the most learned statesmen of the era, he specialized in foreign affairs, working closely with Abraham Lincoln. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. Sumner was a leading proponent of abolishing slavery to weaken the Confederacy. The annexation of Texas - a new slave-holding state - in 1845 pushed Sumner into taking an active role in the anti-slavery movement. He helped organize an alliance between Democrats and the newly created Free-Soil Party in Massachusetts in 1849. His works include The Duel Between France and Germany (1870), Works (1870) and The Best Portraits in Engraving (1875).

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Sumner Charles try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Sumner Charles try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!