Shaw Bernard

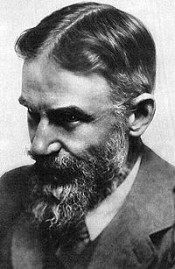

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950) was an Irish playwright. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings deal sternly with prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy to make their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined education, marriage, religion, government, health care and class privilege. He was most angered by the exploitation of the working class, and most of his writings censure that abuse. An ardent socialist, Shaw wrote many brochures and speeches for the Fabian Society. He became an accomplished orator in the furtherance of its causes, which included gaining equal rights for men and women, alleviating abuses of the working class, rescinding private ownership of productive land, and promoting healthy lifestyles. Shaw married Charlotte Payne-Townshend, a fellow Fabian, whom he survived. They settled in Ayot St. Lawrence in a house now called Shaw's Corner. Shaw died there, aged 94, from chronic problems exacerbated by injuries he incurred by falling. He is the only person to have been awarded both a Nobel Prize for Literature (1925) and an Oscar (1938), for his contributions to literature and for his work on the film Pygmalion, respectively.[1] Shaw wanted to refuse his Nobel Prize outright because he had no desire for public honors, but accepted it at his wife's behest: she considered it a tribute to Ireland. He did reject the monetary award, requesting it be used to finance translation of Swedish books to English.[2] George Bernard Shaw was born in Synge Street, Dublin in 1856 to George Carr Shaw (1814–85), whose father was Bernard Shaw, an unsuccessful grain merchant and sometime civil servant, and Lucinda Elizabeth Shaw, née Gurly (1830–1913), a professional singer. He had two sisters, Lucinda Frances (1853–1920), a singer of musical comedy and light opera, and Elinor Agnes (1854–76). George briefly attended the Wesleyan Connexional School, a grammar school operated by the Methodist New Connexion, before moving to a private school near Dalkey and then transferring to Dublin's Central Model School. He ended his formal education at the Dublin English Scientific and Commercial Day School. He harbored a lifelong animosity toward schools and teachers, saying: "Schools and schoolmasters, as we have them today, are not popular as places of education and teachers, but rather prisons and turnkeys in which children are kept to prevent them disturbing and chaperoning their parents".[3] Shaw expressed this attitude in the astringent prologue to Cashel Byron's Profession where young Byron's educational experience is a fictionalized description of Shaw's own schooldays. Later, he painstakingly detailed the reasons for his aversion to formal education in his Treatise on Parents and Children.[4] In brief, he considered the standardized curricula useless, deadening to the spirit and stifling to the intellect. He particularly deplored the use of corporal punishment, which was prevalent in his time. When his mother left home and followed her voice teacher, George Vandeleur Lee, to London, Shaw was almost sixteen years old. His sisters accompanied their mother[5] but Shaw remained in Dublin with his father, first as a reluctant pupil, then as a clerk in an estate office. He worked efficiently, albeit discontentedly, for several years.[6] In 1876, Shaw joined his mother's London household. She, Vandeleur Lee, and his sister Lucy, provided him with a pound a week while he frequented public libraries and the British Museum reading room where he studied earnestly and began writing novels. He earned his allowance by ghostwriting Vandeleur Lee's music column,[7][8] which appeared in the London Hornet. His novels were rejected, however, so his literary earnings remained negligible until 1885, when he became self-supporting as a critic of the arts. Influenced by his reading, he became a dedicated Socialist and a charter member of the Fabian Society,[9] a middle class organization established in 1884 to promote the gradual spread of socialism by peaceful means.[6] In the course of his political activities he met Charlotte Payne-Townshend, an Irish heiress and fellow Fabian; they married in 1898. In 1906 the Shaws moved into a house, now called Shaw's Corner, in Ayot St. Lawrence, a small village in Hertfordshire; it was to be their home for the remainder of their lives, although they also maintained a residence at 29 Fitzroy Square in London. Shaw's plays were first performed in the 1890s. By the end of the decade he was an established playwright. He wrote sixty-three plays and his output as novelist, critic, pamphleteer, essayist and private correspondent was prodigious. He is known to have written more than 250,000 letters.[10] Along with Fabian Society members Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb and Graham Wallas, Shaw founded the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1895 with funding provided by private philanthropy, including a bequest of £20,000 from Henry Hunt Hutchinson to the Fabian Society. One of the libraries at the LSE is named in Shaw's honor; it contains collections of his papers and photographs.[11] During his final years, Shaw enjoyed attending to the grounds at Shaw's Corner. He died at the age of 94, of renal failure precipitated by injuries incurred by falling while pruning a tree.[12] His ashes, mixed with those of his wife, were scattered along footpaths and around the statue of Saint Joan in their garden.[13] The International Shaw Society provides a detailed chronological listing of Shaw's writings.[14] See also George Bernard Shaw, Unity Theatre.[15] View Shaw's Works for listings of his novels and plays, with links to their electronic texts, if those exist. Shaw became a critic of the arts when, sponsored by William Archer, he joined the reviewing staff of the Pall Mall Gazette in 1885.[16] There he wrote under the pseudonym "Corno di Bassetto" ("basset horn")—chosen because it sounded European and nobody knew what a corno di basseto was. In a miscellany of other periodicals, including Dramatic Review (1885–86), Our Corner (1885–86), and the Pall Mall Gazette (1885–88) his byline was "GBS".[17] From 1895 to 1898, Shaw was the drama critic for Frank Harris' Saturday Review, in which position he campaigned brilliantly to displace the artificialities and hypocrisies of the Victorian stage with a theater of actuality and thought. His earnings as a critic made him self-supporting as an author and his articles for the Saturday Review made his name well-known. He had a very high regard for both Irish stage actor Barry Sullivan's and Johnston Forbes-Robertson's Hamlets, but despised John Barrymore's. Barrymore invited him to see a performance of his celebrated Hamlet, and Shaw graciously accepted, but wrote Barrymore a withering letter in which he all but tore the performance to shreds. Even worse, Shaw had seen the play in the company of Barrymore's then-wife, but did not dare voice his true feelings about the performance aloud to her.[18] Much of Shaw's music criticism, ranging from short comments to the book-length essay The Perfect Wagnerite, extols the work of the German composer Richard Wagner.[19] Wagner worked 25 years composing Der Ring des Nibelungen, a massive four-part musical dramatization drawn from the Teutonic mythology of gods, giants, dwarves and Rhine maidens; Shaw considered it a work of genius and reviewed it in detail. Beyond the music, he saw it as an allegory of social evolution where workers, driven by "the invisible whip of hunger", seek freedom from their wealthy masters. Wagner did have socialistic sympathies, as Shaw carefully points out, but made no such claim about his opus. Conversely, Shaw disparaged Brahms, deriding A German Requiem by saying "it could only have come from the establishment of a first-class undertaker".[20] Although he found Brahms lacking in intellect, he praised his musicality, saying "...nobody can listen to Brahms' natural utterance of the richest absolute music, especially in his chamber compositions, without rejoicing in his natural gift".[19] Shaw's writings about music gained great popularity because they were understandable and fair, as well as pleasantly light-hearted and free of affectation, thus contrasting starkly with the dourly pretentious pedantry of most critiques in that era.[21] All of his music critiques have been collected in Shaw's Music.[22] As a drama critic for the Saturday Review, a post he held from 1895 to 1898, Shaw championed Henrik Ibsen whose realistic plays scandalized the Victorian public. His influential Quintessence of Ibsenism was written in 1891.[23] Shaw wrote five unsuccessful novels at the start of his career between 1879 and 1883. Eventually all were published. The first to be printed was Cashel Byron's Profession (1886),[24] which was written in 1882. Its eponymous character, Cashel, a rebellious schoolboy with an unsympathetic mother, runs away to Australia where he becomes a famed prizefighter. He returns to England for a boxing match, and falls in love with erudite and wealthy Lydia Carew. Lydia, drawn by sheer animal magnetism, eventually consents to marry despite the disparity of their social positions. This breach of propriety is nullified by the unpresaged discovery that Cashel is of noble lineage and heir to a fortune comparable to Lydia's. With those barriers to happiness removed, the couple settles down to prosaic family life with Lydia dominant; Cashel attains a seat in Parliament. In this novel Shaw first expresses his conviction that productive land and all other natural resources should belong to everyone in common, rather than being owned and exploited privately. The book was written in the year when Shaw first heard the lectures of Henry George who advocated such reforms. Written in 1883, An Unsocial Socialist was published in 1887.[25] The tale begins with a hilarious description of student antics at a girl's school then changes focus to a seemingly uncouth laborer who, it soon develops, is really a wealthy gentleman in hiding from his overly affectionate wife. He needs the freedom gained by matrimonial truancy to promote the socialistic cause, to which he is an active convert. Once the subject of socialism emerges, it dominates the story, allowing only space enough in the final chapters to excoriate the idle upper class and allow the erstwhile schoolgirls, in their earliest maturity, to marry suitably.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Back to Methuselah

A Metabiological Pentateuch

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Back to Methuselah

A Metabiological Pentateuch

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Irrational KnotBeing the Second Novel of His Nonage

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

fabianism and the fiscal question an alternative policy

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

dramatic opinions and essays with an apology volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

dramatic opinions and essays by g bernard shaw containing as well a word on th

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a plan of campaign for labor containing the substance of the fabian manifesto e

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Shaw Bernard try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Shaw Bernard try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!