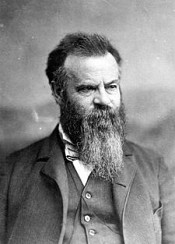

Powell John Wesley

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was a U.S. soldier, geologist, and explorer of the American West. He is famous for the 1869 Powell Geographic Expedition, a three-month river trip down the Green and Colorado rivers that included the first passage through the Grand Canyon. Powell was born in Mount Morris, New York, in 1834, the son of Joseph and Mary Powell. His father, a poor itinerant preacher, had emigrated to the US from Shrewsbury, England in 1830. His family moved westward to Jackson, Ohio, then Walworth County, Wisconsin, then finally settling in Illinois in rural Boone County. He studied at Illinois College, Wheaton College, and Oberlin College, acquiring a knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin but never graduating. Powell had a deep interest in the natural sciences, with a restless nature. As a young man, he undertook a series of adventures through the Mississippi River valley. In 1855 he spent four months walking across Wisconsin. In 1856 he rowed the Mississippi from St. Anthony to the sea, in 1857 he rowed down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to St. Louis, and in 1858 down the Illinois River, then up the Mississippi and the Des Moines River to central Iowa. He was elected to the Illinois Natural History Society in 1859. Due to Powell's deep Protestant beliefs, and his social commitments, his loyalties remained with the Union, and the cause of abolishing slavery, He enlisted in the Union army as a topographer and military engineer.[1] During the Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army, serving first with the 20th Illinois Volunteers. At the Battle of Shiloh, he lost most of one arm when struck by a Minie ball. The raw nerve endings in his arm would continue to cause him pain the rest of his life. Despite the loss of an arm, he bravely returned to the army and was present at Champion Hill and Big Black River Bridge on the Big Black River. Further medical attention to his arm did little to slow him; he was made a major and served as chief of artillery with the 17th Army Corps. In 1862 he married Emma Dean. After leaving the Army he took the post of professor of geology at the Illinois Wesleyan University. He also lectured at Illinois State Normal University, helping found the Illinois Museum of Natural History, where he served as the curator, but declined a permanent appointment in favor of exploration of the American West.[2] From 1867 he led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the Green and Colorado rivers. In 1869 he set out to explore the Colorado and the Grand Canyon. He gathered nine men, four boats and food for ten months and set out from Green River, Wyoming on May 24. Passing through dangerous rapids, the group passed down the Green River to its confluence with the Colorado River (then also known as the Grand River upriver from the junction), near present-day Moab, Utah. The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having ". . . wonderful features—carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds and monuments. From which of these features shall we select a name? We decide to call it Glen Canyon." One man (Goodman) quit after the first month and another three (Dunn and the Howland brothers) left at Separation Rapid in the third, only two days before the group reached the mouth of the Virgin River on August 30, after traversing almost 1,500 km. It is speculated that the three who left the group late in the trip were later killed by the Shivwitz band of the Northern Paiute.[3] However, exactly how and why they died remains a mystery debated by Powell biographers. Some, including Jon Krakauer in his Under the Banner of Heaven, have raised the possibility of a Mormon ambush. The song "Mr. Powell" by the Ozark Mountain Daredevils recounts Powell's trip down the Colorado River. Powell retraced the route in 1871-1872 with another expedition, producing photographs (by John K. Hillers), an accurate map, and various papers. In planning this expedition, he employed the services of Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary in southern Utah and northern Arizona who had cultivated excellent relationships with the Native Americans. Before setting out, Powell used Hamblin as a negotiator to ensure the safety of his expedition from local Indian groups who he believed had killed the three men lost from his previous journey. In 1878, the intellectual gatherings Powell hosted in his home were formalized as the Cosmos Club. In 1881 he became the second director of the US Geological Survey, a post he held until 1894. He was also the director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution until his death. Under his leadership, an influential classification of North American Indian languages was published. [4] In 1875 he published a book based on his explorations of the Colorado originally titled Report of the Exploration of the Columbia River of the West and Its Tributaries, revised and reissued in 1895 as The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons. Powell was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. As an ethnologist and early anthropologist, Powell was a student of the pioneering anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. In his writings, Powell divided human societies into "savagery," "barbarism," and "civilization" based on levels of technology, family and social organization, property relations, and intellectual development. In his view, all societies progressed toward civilization. He was a champion of preservation and conservation. It was his conviction that part of the natural progression of society included a combination of efforts to maximize and make the best use of resources. Powell is credited with coining the word "acculturation," first using it in an 1880 report by the US Bureau of American Ethnography. In 1883, Powell defined "acculturation" to be the psychological changes induced by cross-cultural imitation. Powell' s expeditions led to his belief that the arid west was not suitable for agricultural development, except for about 2% of the lands that were near water sources. His "Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States" proposed irrigation systems and state boundaries based on watershed areas (to avoid squabbles). For the remaining lands he proposed conservation and low density open grazing. The railroad companies, who owned vast tracts of lands (183,000,000 acres) granted in return for building RR lines, did not agree with his opinion. They aggressively lobbied congress to reject Powell's policy proposals and to encourage farming instead. The politicians agreed and developed policies that encouraged pioneer settlement based on agriculture. The basis was the "scientifically proven" theory developed by Professor Cyrus Thomas and promoted by Horace Greeley that agricultural development of land causes arid lands to generate higher amounts of rain ("rain follows the plow"). Powell's recommendations for development of the West were largely ignored until the 1900s, resulting in untold suffering associated with failed pioneer farms resulting from insufficient rain. Clarence King (1879–1881) · John W. Powell (1881–1894) · Charles D. Walcott (1894–1907) · George O. Smith (1907–1930) · Walter C. Mendenhall (1930–1943) · William E. Wrather (1943–1956) · Thomas B. Nolan (1956–1965) · William T. Pecora (1965–1971) · Vincent E. McKelvey (1971–1978) · H. William Menard (1978–1981) · Dallas L. Peck (1981–1993) · Gordon P. Eaton (1994–1997) · Charles G. Groat (1998–2005) · Mark D. Myers (2006–2009) · Marcia McNutt (2009–present)

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Sketch of the Mythology of the North American IndiansFirst Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1879-80,Government Printing Office,Washington,1881,pages 17-56

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On the Evolution of LanguageFirst Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1879-80,Government Printing Office,Washington,1881,pages 1-16

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Indian Linguistic Families Of America,North Of MexicoSeventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1885-1886,Government Printing Office,Washington,1891,pages 1-142

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Sketch of the Mythology of the North American IndiansFirst Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1879-80,Government Printing Office,Washington,1881,pages 17-56

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On the Evolution of LanguageFirst Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1879-80,Government Printing Office,Washington,1881,pages 1-16

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Indian Linguistic Families Of America,North Of MexicoSeventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to theSecretary of the Smithsonian Institution,1885-1886,Government Printing Office,Washington,1891,pages 1-142

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Wyandot Government: A Short Study of Tribal SocietyBureau of American Ethnology

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Wyandot Government: A Short Study of Tribal Society

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Sketch of the Mythology of the North American Indians

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Sketch of the Mythology of the North American Indians: First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879-80, by J.W. Powell, Director, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnography.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On the Evolution of Language

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Investigations in this department are of great interest, and haveattracted to the field a host of workers; but a general review of themass of published matter exhibits the fact that the uses to which thematerial has been put have not always been wise.In the monuments of antiquity found throughout North America, in campand village sites, graves, mounds, ruins, and scattered works of art,the origin and development of art in savage and barbaric life may besatisfactorily studied. Incidentally, too, hints of customs may bediscovered, but outside of this, the discoveries made have often beenillegitimately used, especially for the purpose of connecting the tribesof North America with peoples or so-called races of antiquity in otherportions of the world. A brief review of some conclusions that must beaccepted in the present status of the science will exhibit the futilityof these attempts.It is now an established fact that man was widely scattered over theearth at least as early as the beginning of the quaternary period, and,perhaps, in pliocene time.If we accept the conclusion that there is but one species of man, asspecies are now defined by biologists, we may reasonably conclude thatthe species has been dispersed from some common center, as the abilityto successfully carry on the battle of life in all climes belongs onlyto a highly developed being; but this original home has not yet beenascertained with certainty, and when discovered, lines of migration

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On Limitations To The Use Of Some Anthropologic Data

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Indian Linguistic Families Of America, North Of Mexico

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books / Indians of North America

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Literature & Fiction / Genre Fiction / Fairy Tales

- Books / Different genres / Outdoors & Nature / Hiking & Camping / Excursion Guides / United States

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Books / Administrative agencies

- Books / Indians of North America / Languages

- Books / Child abuse

if you like Powell John Wesley try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books / Indians of North America

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Literature & Fiction / Genre Fiction / Fairy Tales

- Books / Different genres / Outdoors & Nature / Hiking & Camping / Excursion Guides / United States

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Books / Administrative agencies

- Books / Indians of North America / Languages

- Books / Child abuse

if you like Powell John Wesley try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!