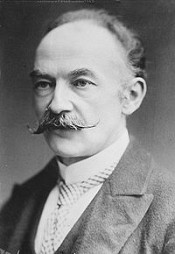

Hardy Thomas

Thomas Hardy, OM (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet of the naturalist movement, although in several poems he displays elements of the previous romantic and enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural. While he regarded himself primarily as a poet and composed novels mainly for financial gain, critical posterity regards him among the most important English novelists. The bulk of his work, set mainly in the semi-fictional land of Wessex, delineates characters struggling against their passions and circumstances. Hardy's poetry, first published in his 50s, has come to be as well regarded as his novels, especially after The Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The term "cliffhanger" is considered to have originated with Thomas Hardy's novel A Pair of Blue Eyes. In this novel Henry Knight, one of his protagonists, is left literally hanging off a cliff. The story, serialized in Tinsley's Magazine between September 1872 and July 1873, became the archetypal — and literal — cliff-hanger of Victorian prose. Thomas Hardy was born at Higher Bockhampton, a hamlet in the parish of Stinsford to the east of Dorchester in Dorset, England. His father (Thomas) worked as a stonemason and local builder. His mother Jemima was well-read and educated Thomas until he went to his first school at Bockhampton at age eight. For several years he attended a school run by a Mr Last. Here he learned Latin and demonstrated academic potential.[1] However, a family of Hardy's social position lacked the means for a university education, and his formal education ended at the age of 16 when he became apprenticed to John Hicks, a local architect. Hardy trained as an architect in Dorchester before moving to London in 1862; there he enrolled as a student at King's College, London. He won prizes from the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Architectural Association. Hardy never felt at home in London. He was acutely conscious of class divisions and his social inferiority. However, he was interested in social reform and was familiar with the works of John Stuart Mill. He was also introduced to the works of Charles Fourier and Auguste Comte during this period by his Dorset friend Horace Moule. Five years later, concerned about his health, he returned to Dorset and decided to dedicate himself to writing. In 1870, while on an architectural mission to restore the parish church of St Juliot in Cornwall,[2] Hardy met and fell in love with Emma Lavinia Gifford, whom he married in 1874.[3][4] Although he later became estranged from his wife, who died in 1912, her death had a traumatic effect on him. After her death, Hardy made a trip to Cornwall to revisit places linked with their courtship, and his Poems 1912–13 reflect upon her passing. In 1914, Hardy married his secretary Florence Emily Dugdale, who was 39 years his junior. However, he remained preoccupied with his first wife's death and tried to overcome his remorse by writing poetry.[5] Hardy became ill with pleurisy in December 1927 and died in January 1928, having dictated his final poem to his wife on his deathbed. His funeral was on 16 January at Westminster Abbey, and it proved a controversial occasion because Hardy and his family and friends had wished for his body to be interred at Stinsford in the same grave as his first wife, Emma. However, his executor, Sir Sydney Carlyle Cockerell, insisted that he be placed in the abbey's famous Poets' Corner. A compromise was reached whereby his heart was buried at Stinsford with Emma, and his ashes in Poets' Corner. Shortly after Hardy's death, the executors of his estate burnt his letters and notebooks. Twelve records survived, one of them containing notes and extracts of newspaper stories from the 1820s. Research into these provided insight into how Hardy kept track of them and how he used them in his later work.[6] In the year of his death Mrs Hardy published The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1841–1891: compiled largely from contemporary notes, letters, diaries, and biographical memoranda, as well as from oral information in conversations extending over many years. Hardy's work was admired by many authors including D. H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf. In his autobiography Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves recalls meeting Hardy in Dorset in the early 1920s. Hardy received him and his newly married wife warmly, and was encouraging about his work. In 1910, Hardy was awarded the Order of Merit. Hardy's cottage at Bockhampton and Max Gate in Dorchester are owned by the National Trust. Hardy's family were Anglican, but not especially devout. He was baptised at the age of five weeks and attended church, where his father and uncle contributed to music. However, he did not attend the local Church of England school, instead being sent to Mr Last's school, three miles away. As a young adult, he befriended Henry R. Bastow (a Plymouth Brethren man), who also worked as a pupil architect, and who was preparing for adult baptism in the Baptist Church, and Hardy flirted with conversion, but decided against it.[7] Bastow went to Australia and maintained a long correspondence with Hardy, but eventually Hardy tired of these exchanges and the correspondence ceased. This concluded Hardy's links with the Baptists. Hardy’s idea of fate in life gave way to his philosophical struggle with God. Although Hardy’s faith remained intact, the irony and struggles of life led him to question the traditional Christian view of God: Hardy's religious life seems to have mixed agnosticism, deism, and spiritism. Once, when asked in correspondence by a clergyman about the question of reconciling the horrors of pain with the goodness of a loving God, Hardy replied, Nevertheless, Hardy frequently conceived of and wrote about supernatural forces that control the universe, more through indifference or caprice than any firm will. Also, Hardy showed in his writing some degree of fascination with ghosts and spirits.[9] Despite these sentiments, Hardy retained a strong emotional attachment to the Christian liturgy and church rituals, particularly as manifested in rural communities, that had been such a formative influence in his early years. In Far From the Madding Crowd, Oak’s entire flock, and livelihood, dies. For Oak, being a simple farmer with nothing to his name, to encounter such a loss is a tragedy wherein Hardy wants his readers to consider the role of God in this type of situation along with the universe’s cruelty. Biblical references can be found woven throughout many of Hardy’s novels as he became friends with a Dorchester minister, Hourace Moule. Moule also influenced Hardy’s point of view by introducing him to scientific studies and ideas that questioned the literal meaning of the Bible.[10] Hardy's first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, finished by 1867, failed to find a publisher and Hardy destroyed the manuscript so only parts of the novel remain. He was encouraged to try again by his mentor and friend, Victorian poet and novelist George Meredith. Desperate Remedies (1871) and Under the Greenwood Tree (1872) were published anonymously. In 1873 A Pair of Blue Eyes, a story drawing on Hardy's courtship of his first wife, was published under his own name. Hardy said that he first introduced Wessex in Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), his next novel. It was successful enough for Hardy to give up architectural work and pursue a literary career. Over the next twenty-five years Hardy produced ten more novels. The Hardys moved from London to Yeovil and then to Sturminster Newton, where he wrote The Return of the Native (1878). In 1885, they moved for a last time, to Max Gate, a house outside Dorchester designed by Hardy and built by his brother. There he wrote The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), The Woodlanders (1887) and Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891), the last of which attracted criticism for its sympathetic portrayal of a "fallen woman" and was initially refused publication. Its subtitle, A Pure Woman: Faithfully Presented, was intended to raise the eyebrows of the Victorian middle-classes. Jude the Obscure, published in 1895, met with even stronger negative outcries from the Victorian public for its frank treatment of sex, and was often referred to as "Jude the Obscene". Heavily criticised for its apparent attack on the institution of marriage through the presentation of such concepts as erotolepsy, the book caused further strain on Hardy's already difficult marriage because Emma Hardy was concerned that Jude the Obscure would be read as autobiographical. Some booksellers sold the novel in brown paper bags, and the Bishop of Wakefield is reputed to have burnt his copy.[6] In his postscript of 1912, Hardy humorously referred to this incident as part of the career of the book: "After these [hostile] verdicts from the press its next misfortune was to be burnt by a bishop — probably in his despair at not being able to burn me".[11] Despite this criticism, Hardy had become a celebrity in English literature by the 1900s, with several highly successful novels behind him, yet he felt disgust at the public reception of two of his greatest works and gave up writing fiction altogether. Although he wrote a great deal of poetry, most of it went unpublished until after 1898, thus Hardy is best remembered for the series of novels and short stories he wrote between 1871 and 1895. His novels are set in the imaginary world of Wessex, a large area of south and south-west England, using the name of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that covered the area. Hardy was part of two worlds. He had a deep emotional bond with the rural way of life which he had known as a child, but he was also aware of the changes which were under way and the current social problems, from the innovations in agriculture — he captured the epoch just before the Industrial Revolution changed the English countryside — to the unfairness and hypocrisy of Victorian sexual behaviour. Hardy critiques certain social constraints that hindered the lives of those living in the 19th century. Considered a Victorian Realist writer, Hardy examines the social constraints that are part of the Victorian status quo, suggesting these rules hinder the lives of all involved and ultimately lead to unhappiness. In Two on a Tower, Hardy seeks to take a stand against these rules and sets up a story against the backdrop of social structure by creating a story of love that crosses the boundaries of class. The reader is forced to consider disposing of the conventions set up for love. Nineteenth-century society enforces these conventions, and societal pressure ensures conformity. Swithin St Cleeve's idealism pits him against contemporary social constraints. He is a self-willed individual set up against the coercive strictures of social rules and mores.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

a school in action data on children artists and teachers

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

a school in action data on children artists and teachers

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Under the Greenwood Tree, or, the Mellstock quire; a rural painting of the Dutch school

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Collection of poems from the famous English novelist, short story writer, and poet of the naturalist movement, who was awarded the Order of Merit in 1910. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Satires of Circumstance, lyrics and reveries with miscellaneous pieces

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Literature & Fiction / Classics / General AAS

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (D) / Dumas, Alexandre

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (H) / Hardy, Thomas

- Books / Hardy, Thomas,1840-1928

- Books / Hardy, Thomas / 1840-1928

if you like Hardy Thomas try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Literature & Fiction / Classics / General AAS

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (D) / Dumas, Alexandre

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (H) / Hardy, Thomas

- Books / Hardy, Thomas,1840-1928

- Books / Hardy, Thomas / 1840-1928

if you like Hardy Thomas try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!