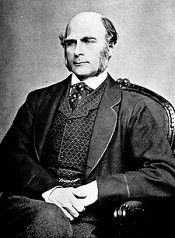

Galton Francis Sir

Sir Francis Galton FRS (16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), cousin of Sir Douglas Galton, was an English Victorian polymath, anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, psychometrician, and statistician. He was knighted in 1909. Galton had a prolific intellect, and produced over 340 papers and books throughout his lifetime. He also created the statistical concept of correlation and widely promoted regression toward the mean. He was the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human differences and inheritance of intelligence, and introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys for collecting data on human communities, which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for his anthropometric studies. He was a pioneer in eugenics, coining the very term itself and the phrase "nature versus nurture." As an investigator of the human mind, he founded psychometrics (the science of measuring mental faculties) and differential psychology. He devised a method for classifying fingerprints that proved useful in forensic science. As the initiator of scientific meteorology, he devised the first weather map, proposed a theory of anticyclones, and was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale.[1] He also invented the Galton Whistle for testing differential hearing ability. He was born at "The Larches", a large house in Sparkbrook, Birmingham, Warwickshire, England, built on the site of "Fair Hill", the former home of Joseph Priestley, which the botanist William Withering had renamed. He was Charles Darwin's half-cousin, sharing the common grandparent Erasmus Darwin. His father was Samuel Tertius Galton, son of Samuel "John" Galton. The Galtons were famous and highly successful Quaker gun-manufacturers and bankers, while the Darwins were distinguished in medicine and science. Both families boasted Fellows of the Royal Society and members who loved to invent in their spare time. Both Erasmus Darwin and Samuel Galton were founder members of the famous Lunar Society of Birmingham, whose members included Boulton, Watt, Wedgwood, Priestley, Edgeworth, and other distinguished scientists and industrialists. Likewise, both families boasted literary talent, with Erasmus Darwin notorious for composing lengthy technical treatises in verse, and Aunt Mary Anne Galton known for her writing on aesthetics and religion, and her notable autobiography detailing the unique environment of her childhood populated by Lunar Society members. Galton was by many accounts a child prodigy — he was reading by the age of 2, at age 5 he knew some Greek, Latin and long division, and by the age of six he had moved on to adult books, including Shakespeare for pleasure, and poetry, which he quoted at length (Bulmer 2003, p. 4). Later in life, Galton would propose a connection between genius and insanity based on his own experience. He stated, “Men who leave their mark on the world are very often those who, being gifted and full of nervous power, are at the same time haunted and driven by a dominant idea, and are therefore within a measurable distance of insanity” [2] Throughout his life, Galton attended numerous schools, but chafed at the narrow classical curriculum. His parents pressed him to enter the medical profession, and he studied for two years at Birmingham General Hospital and King's College, London Medical School. He followed this up with mathematical studies at Trinity College, University of Cambridge, from 1840 to early 1844.[3] A severe nervous breakdown altered his original intention to try for honours. He elected instead to take a "poll" (pass) B.A. degree, like his cousin Charles Darwin (Bulmer 2003, p. 5). (Following the Cambridge custom, he was awarded an M.A. without further study, in 1847). He then briefly resumed his medical studies. The death of his father in 1844 left him financially independent but emotionally destitute, and he terminated his medical studies entirely, turning to foreign travel, sport and technical invention. In his early years Galton was an enthusiastic traveller, and made a notable solo trip through Eastern Europe to Constantinople, before going up to Cambridge. In 1845 and 1846 he went to Egypt and travelled down the Nile to Khartoum in the Sudan, and from there to Beirut, Damascus and down the Jordan. In 1850 he joined the Royal Geographical Society, and over the next two years mounted a long and difficult expedition into then little-known South West Africa (now Namibia). He wrote a successful book on his experience, "Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa". He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's gold medal in 1853 and the Silver Medal of the French Geographical Society for his pioneering cartographic survey of the region (Bulmer 2003, p. 16). This established his reputation as a geographer and explorer. He proceeded to write the best-selling The Art of Travel, a handbook of practical advice for the Victorian on the move, which went through many editions and still reappears in print today. Galton was a polymath who made important contributions in many fields of science, including meteorology (the anti-cyclone and the first popular weather maps), statistics (regression and correlation), psychology (synaesthesia), biology (the nature and mechanism of heredity), and criminology (fingerprints). Much of this was influenced by his penchant for counting or measuring. Galton prepared the first weather map published in The Times (1 April 1875, showing the weather from the previous day, 31 March), now a standard feature in newspapers worldwide.[4] He became very active in the British Association for the Advancement of Science, presenting many papers on a wide variety of topics at its meetings from 1858 to 1899 (Bulmer 2003, p. 29). He was the general secretary from 1863 to 1867, president of the Geographical section in 1867 and 1872, and president of the Anthropological Section in 1877 and 1885. He was active on the council of the Royal Geographical Society for over forty years, in various committees of the Royal Society, and on the Meteorological Council. The publication by his cousin Charles Darwin of The Origin of Species in 1859 was an event that changed Galton's life. He came to be gripped by the work, especially the first chapter on "Variation under Domestication" concerning the breeding of domestic animals. An interesting fact, not widely known, is that Galton was present to hear the famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate at the British Association. The evidence for this comes from his wife Louisa's Annual Record for 1860.[5] Galton devoted much of the rest of his life to exploring variation in human populations and its implications, at which Darwin had only hinted. In doing so, he eventually established a research programme which embraced many aspects of human variation, from mental characteristics to height, from facial images to fingerprint patterns. This required inventing novel measures of traits, devising large-scale collection of data using those measures, and in the end, the discovery of new statistical techniques for describing and understanding the data. Galton was interested at first in the question of whether human ability was hereditary, and proposed to count the number of the relatives of various degrees of eminent men. If the qualities were hereditary, he reasoned, there should be more eminent men among the relatives than among the general population. He obtained his data from various biographical sources and compared the results that he tabulated in various ways. This pioneering work was described in detail in his book [6] in 1869. He showed, among other things, that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when going from the first degree to the second degree relatives, and from the second degree to the third. He took this as evidence of the inheritance of abilities. He also proposed adoption studies, including trans-racial adoption studies, to separate out the effects of heredity and environment. The method used in Hereditary Genius has been described as the first example of historiometry. To bolster these results, and to attempt to make a distinction between 'nature' and 'nurture' (he was the first to apply this phrase to the topic), he devised a questionnaire that he sent out to 190 Fellows of the Royal Society. He tabulated characteristics of their families, such as birth order and the occupation and race of their parents. He attempted to discover whether their interest in science was 'innate' or due to the encouragements of others. The studies were published as a book, English men of science: their nature and nurture, in 1874. In the end, it promoted the nature versus nurture question, though it did not settle it, and provided some fascinating data on the sociology of scientists of the time. Galton recognized the limitations of his methods in these two works, and believed the question could be better studied by comparisons of twins. His method was to see if twins who were similar at birth diverged in dissimilar environments, and whether twins dissimilar at birth converged when reared in similar environments. He again used the method of questionnaires to gather various sorts of data, which were tabulated and described in a paper The history of twins in 1875. In so doing he anticipated the modern field of behavior genetics, which relies heavily on twin studies. He concluded that the evidence favored nature rather than nurture. Galton invented the term eugenics in 1883 and set down many of his observations and conclusions in a book, Inquiries into human faculty and its development.[7] He believed that a scheme of 'marks' for family merit should be defined, and early marriage between families of high rank be encouraged by provision of monetary incentives. He pointed out some of the tendencies in British society, such as the late marriages of eminent people, and the paucity of their children, which he thought were dysgenic. He advocated encouraging eugenic marriages by supplying able couples with incentives to have children. Galton's study of human abilities ultimately led to the foundation of differential psychology and the formulation of the first mental tests.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1883. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1883. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Galton Francis Sir try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Galton Francis Sir try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!