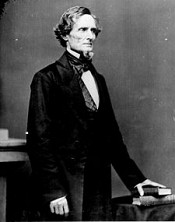

Davis Jefferson

Jefferson Finis Davis (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as President of the Confederate States of America for its entire history, 1861 to 1865, during the American Civil War. A West Point graduate, Davis fought in the Mexican-American War as a colonel of a volunteer regiment, and was the United States Secretary of War under Franklin Pierce. Both before and after his time in the Pierce Administration, he served as a U.S. Senator from Mississippi. As a senator he argued against secession but believed each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union. Davis resigned from the Senate in January 1861[1] , after receiving word that Mississippi had seceded from the Union. The following month, he was provisionally appointed President of the Confederate States of America. He was elected to a six-year term that November. During his presidency, Davis was not able to find a strategy to defeat the more industrially developed Union. After Davis was captured May 10, 1865, he was charged with treason, though not tried, and stripped of his eligibility to run for public office. This limitation was posthumously removed by order of Congress and President Jimmy Carter in 1978, 89 years after his death. While not disgraced, he was displaced in Southern affection after the war by its leading general, Robert E. Lee. Davis was the youngest of the ten children of Samuel Emory Davis (Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1756 – July 4, 1824) and wife (married 1783) Jane Cook (Christian County, (later Todd County), Kentucky, 1759 – October 3, 1845), daughter of William Cook and wife Sarah Simpson, daughter of Samuel Simpson (1706 – 1791) and wife Hannah (b. 1710). The younger Davis's grandfather, Evan Davis (Cardiff, County Glamorgan, 1729 – 1758), emigrated from Wales and had once lived in Virginia and Maryland, marrying Lydia Emory. His father, along with his uncles, had served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War; he fought with the Georgia cavalry and fought in the Siege of Savannah as an infantry officer. Also, three of his older brothers served during the War of 1812. Two of them served under Andrew Jackson and received commendation for bravery in the Battle of New Orleans. During Davis's youth, the family moved twice; in 1811 to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, and in 1812 to Wilkinson County, Mississippi near the town of Woodville. In 1813, Davis began his education together with his sister Mary, attending a log cabin school a mile from their home in the small town of Woodville, known as the Wilkinson Academy. Two years later, Davis entered the Catholic school of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory, a school operated by the Dominican Order in Washington County, Kentucky. At the time, he was the only Protestant student. Davis went on to Jefferson College at Washington, Mississippi, in 1818, and to Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1821. In 1824, Davis entered the United States Military Academy (West Point).[2] He completed his four-year term as a West Point cadet, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in June 1828 following graduation.[3] Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Wisconsin. His first assignment, in 1829, was to supervise the cutting of timber on the banks of the Red Cedar River for the repair and enlargement of the fort. Later the same year, he was reassigned to Fort Winnebago. While supervising the construction and management of a sawmill along the Yellow River in Iowa in 1831, he contracted pneumonia, causing him to return to Fort Crawford.[4] The year after, Davis was dispatched to Galena, Illinois, at the head of a detachment assigned to remove miners from lands claimed by the Native Americans. Lieutenant Davis was home in Mississippi for the entire Black Hawk War, returning after the Battle of Bad Axe. Following the conflict, he was assigned by his colonel, Zachary Taylor, to escort Black Hawk himself to prison—it is said that the chief liked Davis because of the kind treatment he had shown. Another of Davis's duties during this time was to keep miners from illegally entering what would eventually become the state of Iowa. Davis fell in love with Zachary Taylor's daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor. Her father did not approve of the match, so Davis resigned his commission and married Miss Taylor on June 17, 1835, at the house of her aunt near Louisville, Kentucky. The marriage, however, proved to be short. While visiting Davis's oldest sister near Saint Francisville, Louisiana, both newlyweds contracted malaria, and Davis's wife died three months after the wedding on September 15, 1835. In 1836, he moved to Brierfield Plantation in Warren County, Mississippi. For the next eight years, Davis was a recluse, studying government and history, and engaging in private political discussions with his brother Joseph.[2] The year 1844 saw Davis's first political success, as he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, taking office on March 4 of the following year. In 1845, Davis married Varina Howell, the granddaughter of late New Jersey Governor Richard Howell whom he met the year before, at her home in Natchez, Mississippi. Jefferson and Varina Howell Davis had 6 children, but only 1 survived young adulthood and married: There is a portrait of Mrs. Jefferson Davis in old age at the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library in Biloxi, Mississippi, painted by Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862-1947) in 1895 and dubbed 'Widow of the Confederacy'. It was exhibited at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in New York in 1897. The Museum of the Confederacy at Richmond, Virginia, possesses Müller-Ury's 1897-98 profile portrait of their daughter Winnie Davis which the artist presented to the Museum in 1918. In 1846, the Mexican-American War began. Davis resigned his House seat in June, and raised a volunteer regiment, the Mississippi Rifles, becoming its colonel.[5] On July 21, 1846, they sailed from New Orleans for the Texas coast. Davis armed the regiment with percussion rifles and trained the regiment in their use, making it particularly effective in combat.[6] In September 1846, Davis participated in the successful siege of Monterrey.[7] On February 22, 1847, Davis fought bravely at the Battle of Buena Vista and was shot in the foot, being carried to safety by Robert H. Chilton. In recognition of Davis's bravery and initiative, commanding general Zachary Taylor is reputed to have said: "My daughter, sir, was a better judge of men than I was."[2] On May 17th, 1847, President James K. Polk offered[8] Davis a Federal commission as a brigadier general and command of a brigade of militia. He declined the appointment, however, arguing that the United States Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, and not to the Federal government of the United States.[9] Because of his war service, the governor of Mississippi appointed Davis to fill out the Senate term of the late Jesse Speight. He took his seat December 5, 1847, and was elected to serve the remainder of his term in January 1848. In addition, the Smithsonian Institution appointed him a regent at the end of December 1847. Davis introduced an amendment to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to annex most of northeastern Mexico. It failed 44-11. The Senate made Davis chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs. When his term expired, he was elected to the same seat (by the Mississippi legislature, as the Constitution mandated at the time). He had not served a year when he resigned (in September 1851) to run for the Governorship of Mississippi on the issue of the Compromise of 1850, which Davis opposed. This election bid was unsuccessful, as he was defeated by fellow senator Henry Stuart Foote by 999 votes.[10] Left without political office, Davis continued his political activity. He took part in a convention on states' rights, held at Jackson, Mississippi in January 1852. In the weeks leading up to the presidential election of 1852, he campaigned in numerous Southern states for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce and William R. King. Pierce won the election and, in 1853, made Davis his Secretary of War.[11] In this capacity, Davis gave to Congress four annual reports (in December of each year), as well as an elaborate one (submitted on February 22, 1855) on various routes for the proposed Transcontinental Railroad, and promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona from Mexico. The Pierce Administration ended in 1857. The President lost the Democratic nomination, which went instead to James Buchanan. Davis's term was to end with Pierce's, so he ran successfully for the Senate, and re-entered it on March 4, 1857. His renewed service in the Senate was interrupted by an illness that threatened him with the loss of his left eye. Still nominally serving in the Senate, Davis spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. On the Fourth of July, he delivered an anti-secessionist speech on board a ship near Boston. He again urged the preservation of the Union on October 11 in Faneuil Hall, Boston, and returned to the Senate soon after. As Davis explained in his memoir The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, he believed that each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union. He counseled delay among his fellow Southerners, however, because he did not think that the North would permit the peaceable exercise of the right to secession. Having served as Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce, he also knew that the South lacked the military and naval resources necessary to defend itself if war were to break out. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, however, events accelerated. South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860, and Mississippi did so on January 9, 1861. As soon as Davis received official notification of that fact, he delivered a farewell address to the United States Senate, resigned, and returned to Mississippi. Four days after his resignation, Davis was commissioned a Major General of Mississippi troops.[2] On February 9, 1861, a Constitutional convention at Montgomery, Alabama named him provisional President of the Confederate States of America and he was inaugurated on February 18, 1861. In meetings of his own Mississippi legislature, Davis had argued against secession, but when a majority of the delegates opposed him, he gave in.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

speech of the hon jefferson davis of mississippi delivered in the united stat

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

speech of mr davis of mississippi on the subject of slavery in the territorie

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

speech of hon jefferson davis of mississippi on his resolutions relative to t

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

speech of the hon jefferson davis of mississippi delivered in the united stat

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

speech of mr davis of mississippi on the subject of slavery in the territorie

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

speech of hon jefferson davis of mississippi on his resolutions relative to t

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

reply of hon jefferson davis of mississippi to the speech of senator douglas

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Speeches of the Hon. Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi; delivered during the summer of 1858.

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

This volume is produced from digital images from the Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Davis Jefferson try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Davis Jefferson try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!