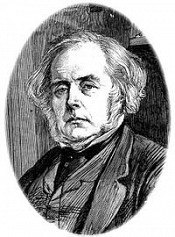

Bright John

John Bright PC (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889), Quaker, was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, associated with Richard Cobden in the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League. He was one of the greatest orators of his generation, and a strong critic of British foreign policy. Bright was born at Rochdale, Lancashire, England — one of the early centres of the Industrial Revolution. His father, Jacob Bright, was a much-respected Quaker, who had started a cotton mill at Rochdale in 1809. His own father, Abraham Bright, had been a Wiltshire yeoman, who, early in the 18th century, removed to Coventry, where his descendants remained. Jacob Bright had been educated at the Ackworth School of the Society of Friends, and apprenticed to a fustian manufacturer at New Mills, Derbyshire. John Bright was his son by his second wife, Martha Wood, daughter of a Quaker shopkeeper of Bolton-le-Moors. Educated at Ackworth School, she was a woman of great strength of character and refined taste. There were eleven children of this marriage, of whom John was the eldest surviving son. His sisters included Priscilla Bright (whose husband was Duncan McLaren MP) and Margaret Bright Lucas. John was a delicate child, and was sent as a day pupil to a boarding school near his home, kept by William Littlewood. A year at the Ackworth School, two years at Bootham School, York, and a year and a half at Newton, near Clitheroe, completed his education. He learned, he himself said, but little Latin and Greek, but acquired a great love of English literature, which his mother fostered, and a love of outdoor pursuits. In his sixteenth year, he entered his father's mill, and in due time became a partner in the business. In Rochdale, Jacob Bright was a leader of the opposition to a local church-rate. Rochdale was also prominent in the movement for parliamentary reform, by which the town successfully claimed to have a member allotted to it under the Reform Bill. John Bright took part in both campaigns. He was an ardent Nonconformist, proud to number among his ancestors John Gratton, a friend of George Fox, and one of the persecuted and imprisoned preachers of the Religious Society of Friends. His political interest was probably first kindled by the Preston election in 1830, in which Edward Stanley, after a long struggle, was defeated by Henry "Orator" Hunt. But it was as a member of the Rochdale Juvenile Temperance Band that he first learned public speaking. These young men went out into the villages, borrowed a chair of a cottager, and spoke from it at open-air meetings. John Bright's first extempore speech was at a temperance meeting. Bright got his notes muddled, and broke down. The chairman gave out a temperance song, and during the singing told Bright to put his notes aside and say what came into his mind. Bright obeyed, began with much hesitancy, but found his tongue and made an excellent address. On some early occasions, however, he committed his speech to memory. In 1832 he called on the Rev. John Aldis, an eminent Baptist minister, to accompany him to a local Bible meeting. Mr Aldis described him as a slender, modest young gentleman, who surprised him by his intelligence and thoughtfulness, but who seemed nervous as they walked to the meeting together. At the meeting he made a stimulating speech, and on the way home asked for advice. Mr Aldis counselled him not to learn his speeches, but to write out and commit to memory certain passages and the peroration. This "first lesson in public speaking," as Bright called it, was given in his twenty-first year, but he had not then contemplated a public career. He was a fairly prosperous man of business, very happy in his home, always ready to take part in the social, educational and political life of his native town. A founder of the Rochdale Literary and Philosophical Society, he took a leading part in its debates, and on returning from a holiday journey in the east, gave the society a lecture on his travels. He first met Richard Cobden in 1836 or 1837. Cobden was an alderman of the newly formed Manchester Corporation, and Bright went to ask him to speak at an education meeting in Rochdale. Cobden consented, and at the meeting was much struck by Bright's short speech, and urged him to speak against the Corn Laws. His first speech on the Corn Laws was made at Rochdale in 1838, and in the same year he joined the Manchester provisional committee which in 1839 founded the Anti-Corn Law League He was still only the local public man, taking part in all public movements, especially in opposition to John Feilden's proposed factory legislation, and to the Rochdale church-rate. In 1839 he built the house which he called "One Ash", and married Elizabeth, daughter of Jonathan Priestman of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In November of the same year there was a dinner in Bolton in honour of Abraham Paulton, who had just returned from an unsuccessful Anti-Corn Law tour in Scotland. Among the speakers were Cobden and Bright, and the dinner is memorable as the first occasion on which the two future leaders appeared together on a Free Trade platform. Bright is described by the historian of the League as "a young man then appearing for the first time in any meeting out of his own town, and giving evidence, by his energy and by his grasp of the subject, of his capacity soon to take a leading part in the great agitation." In 1840 he led a movement against the Rochdale church-rate, speaking from a tombstone in the churchyard, where it looks down on the town in the valley below. A daughter, Helen, was born to him; but his young wife, after a long illness, died of tuberculosis in September, 1841. Three days after her death at Leamington, Cobden called to see him. "I was in the depths of grief," said Bright, when unveiling the statue of his friend at Bradford in 1877, "I might almost say of despair, for the life and sunshine of my house had been extinguished." Cobden spoke some words of condolence, but "after a time he looked up and said, 'There are thousands of homes in England at this moment where wives, mothers and children are dying of hunger. Now, when the first paroxysm of your grief is past, I would advise you to come with me, and we will never rest till the Corn Laws are repealed.' I accepted his invitation," added Bright, "and from that time we never ceased to labour hard on behalf of the resolution which we had made." At the general election in 1841 Cobden was returned for Stockport, Cheshire and in 1843 Bright was the Free Trade candidate at a by-election at Durham. He was defeated, but his successful competitor was unseated on petition, and at the second contest Bright was returned. He was already known as Cobden's chief ally, and was received in the House of Commons with suspicion and hostility. In the Anti-Corn Law movement the two speakers complemented of each other. Cobden had the calmness and confidence of the political philosopher, Bright had the passion and the fervour of the popular orator. Cobden did the reasoning, Bright supplied the declamation, but mingled argument with appeal. No orator of modern times rose more rapidly. He was not known beyond his own borough when Cobden called him to his side in 1841, and he entered parliament towards the end of the session of 1843 with a formidable reputation. He had been all over England and Scotland addressing vast meetings and, as a rule, carrying them with him; he had taken a leading part in a conference held by the Anti-Corn Law League in London had led deputations to the Duke of Sussex, to Sir James Graham, then home secretary, and to Lord Ripen and Gladstone, the secretary and under secretary of the Board of Trade; and he was universally recognised as the chief orator of the Free Trade movement. Wherever "John Bright of Rochdale" was announced to speak, vast crowds assembled. He had been so announced, for the last time, at the first great meeting in Drury Lane Theatre on 15 March 1843; henceforth his name was enough. He took his seat in the House of Commons as one of the members for Durham on 28 July 1843, and on 7 August delivered his maiden speech in support of a motion by Mr Ewart for reduction of import duties. He was there, he said, "not only as one of the representatives of the city of Durham, but also as one of the representatives of that benevolent organisation, the Anti-Corn Law League." A member who heard the speech described Bright as "about the middle size, rather firmly and squarely built, with a fair, clear complexion, and an intelligent and pleasing expression of countenance. His voice is good, his enunciation distinct, and his delivery free from any unpleasant peculiarity or mannerism." He wore the usual Friend's coat, and was regarded with much interest and hostile curiosity on both sides of the House. Mr Ewart's motion was defeated, but the movement of which Cobden and Bright were the leaders continued to spread. In the autumn the League resolved to raise £100,000; an appeal was made to the agricultural interest by great meetings in the farming counties, and in November The Times startled the country by declaring, in a leading article, "The League is a great fact. It would be foolish, nay, rash, to deny its importance." In London great meetings were held in Covent Garden Theatre, at which William Johnson Fox was the chief orator, but Bright and Cobden were the leaders of the movement. Bright publicly deprecated the popular tendency to regard Cobden and himself as the chief movers in the agitation, and Cobden told a Rochdale audience that he always stipulated that he should speak first, and Bright should follow. His "more stately genius," as John Morley calls it, was already making him the undisputed master of the feelings of his audiences. In the House of Commons his progress was slower. Cobden's argumentative speeches were regarded more sympathetically than Bright's more rhetorical appeals, and in a debate on George Villiers's annual motion against the Corn Laws, Bright was heard with so much impatience that he was obliged to sit down. In the next session (1845) he moved for an inquiry into the operation of the Game Laws. At a meeting of county members earlier in the day Robert Peel, then Prime Minister, had advised them not to be led into discussion by a violent speech from the member for Durham, but to let the committee be granted without debate. Bright was not violent, and Cobden said that he did his work admirably, and won golden opinions from all men. The speech established his position in the House of Commons. In this session Bright and Cobden came into opposition, Cobden voting for the Maynooth Grant and Bright against it. On only one other occasion—a vote for South Kensington—did they go into opposite lobbies, during twenty-five years of parliamentary life.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Volume 1. please visit www.valdebooks.com for a full list of titles

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Volume 1. please visit www.valdebooks.com for a full list of titles

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Bright John try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Bright John try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!