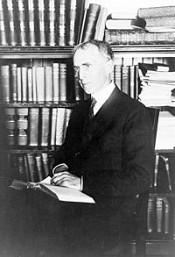

Beard Charles Austin

Charles Austin Beard (November 27, 1874 – September 1, 1948) was an American historian. He published hundreds of monographs, textbooks and interpretive studies in both history and political science. His works included radical re-evaluation of the Founding Fathers of the United States, who he believed were more motivated by economics than by philosophical principles. As a leader of the "progressive historians," or "progressive historiography," he introduced themes of economic self-interest and economic conflict regarding the adoption of the Constitution and the transformations caused by the Civil War. Thus he emphasized the long-term conflict among industrialists in the Northeast, farmers in the Midwest, and planters in the South that he saw as the cause of the Civil War. His study of the financial interests of the drafters of the United States Constitution (An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution) seemed radical in 1913, since he proposed that the U.S. Constitution was a product of economically determinist, land-holding founding fathers. He saw ideology as a product of economic interests. Beard's most influential book was the wide-ranging and bestselling The Rise of American Civilization (1927) and its two sequels, America in Midpassage (1939), and The American Spirit (1943), written with his wife, Mary. Historian Carl Becker in History of Political Parties in the Province of New York, 1760-1776 (1909) formulated the Progressive interpretation of the American Revolution. He said there were two revolutions: one against Britain to obtain home rule, and the other to determine who should rule at home. Beard expanded upon Becker's thesis, in terms of class conflict, in An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913) and An Economic Interpretation of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915). To Beard, the Constitution was a counter-revolution, set up by rich bondholders (personalty; bonds were "personal property"), in opposition to the farmers and planters (realty; land was "real property.") Beard argued the Constitution was designed to reverse the radical democratic tendencies unleashed by the Revolution among the common people, especially farmers and debtors. In 1800, said Beard, the farmers and debtors, led by plantation slave owners, overthrew the capitalists and established Jeffersonian democracy. Other historians supported the class-conflict interpretation, noting the states confiscated great semi-feudal landholdings of loyalists and gave them out in small parcels to ordinary farmers. Conservatives, such as William Howard Taft, were shocked at the Progressive interpretation because it seemed to belittle the Constitution.[1] Many scholars, however, eventually adopted Beard's thesis and by 1950 it had become the standard interpretation of the era. Beginning about 1950, however, historians started to argue that the progressive interpretation was factually incorrect.[2]Template:Clarify source Forrest McDonald in We The People: The Economic Origins of the Constitution (1958) argued that Charles Beard had misinterpreted the economic interests involved in writing the Constitution. Instead of two interests, landed and mercantile, which conflicted, there were three dozen identifiable interests that forced the delegates to bargain. Controversy raged, but by 1970 the Progressive interpretation of the era was dead. It was largely replaced by the intellectual history approach, which stressed the power of ideas, especially republicanism, in stimulating the Revolution.[3] However, the legacy of examining the economic interests of American historical actors remains enduring. Dealing with Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, disciples of Beard such as Howard Beale and C. Vann Woodward focused on greed and economic causation and emphasized the centrality of corruption. They argued that the rhetoric of equal rights was a smokescreen hiding their true motivation, which was promoting the interests of industrialists in the Northeast. The basic flaw was the assumption that there was a unified business policy. Scholars in the 1950s and 1960s demonstrated that businessmen were widely divergent on monetary or tariff policy. While Pennsylvania businessmen wanted high tariffs, those in other states did not; the railroads were hurt by the tariffs on steel, which they purchased in large quantity.[4] Beard's economic approach lost influence in the history profession after 1950 as conservative scholars suggested serious flaws in Beard's research, and attention turned away from economic causation.[5] Beard's interest in progressive higher education was an early one. In 1899, he collaborated with Walter Vrooman at Oxford in the founding of Ruskin Hall, which was billed as an accessible school for the working man. In exchange for considerable reduction in tuition, students worked in the school's various businesses. After resigning from Columbia University in protest in 1917, he helped to found the New School for Social Research in New York, and advised on reconstructing Tokyo after the earthquake of 1923. Although enormously influential through his massive writings, he did not have graduate students or build a school of historiography. Beard attended and graduated from DePauw University in 1898. It was at DePauw that he met Mary Ritter. They later were married. Many of his books were written in collaboration with his wife, whose own interests lay in feminism and the labor union movement (Woman as a Force in History, 1946). Together they wrote a popular survey, The Beards: Basic History of the United States. Starting as a leading liberal supporter of the New Deal, Beard turned against Franklin Delano Roosevelt's foreign policy. Beard promoted "American Continentalism," arguing that the United States had no vital stake in Europe and that a foreign war would threaten dictatorship at home. Beard was thus one of the leading proponents of American non-interventionism. After the war, Beard's last work, President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War (1948), blamed Roosevelt for lying to the American people and tricking them into war. It generated angry controversy as internationalists denounced Beard as an apologist for isolationism. As a result, Beard's reputation collapsed among liberal historians who previously had admired him. His whole interpretation of history came under widespread attack, though a few leading historians such as Beale and Woodward clung to the Beardian interpretation of American history. Recently, however, Beard's isolationist approach, especially his advocacy of a non-interventionist foreign policy, has enjoyed something of a comeback. Andrew Bacevich, a historian of diplomacy from Boston University, has used Beard's skepticism towards armed intervention overseas as a starting point for his own critique of post-Cold-War American foreign policy; Beard is heavily cited in Bacevich's analysis of this policy, American Empire. In addition, Beard's foreign policy views have become popular with supporters of paleoconservatism, such as Pat Buchanan. Beard's stress on economic causation influenced the "Wisconsin school" of New Left, or revisionist, historians William Appleman Williams, Gabriel Kolko, and James Weinstein. In the field of political science, Beard was active in the American Political Science Association and was elected its President in 1926.[6] He was also a member of the American Historical Association and served as its president in 1933.[7] He was best known for his studies of the Constitution, and for his creation of bureaus of municipal research and his studies of public administration in cities, including a famous study of Tokyo, The Administration and Politics of Tokyo, (1923). A White · Bancroft · Winsor · Poole · CK Adams · Jay · Henry · Angell · H Adams · Hoar · Storrs · Schouler · Fisher · Rhodes · Eggleston · CF Adams · Mahan · Lea · Smith · McMaster · Baldwin · Jameson · G Adams · Hart · Turner · Sloane · Roosevelt · Dunning · McLaughlin · Stephens · Burr · Ford · Thayer · Channing · Jusserand · Haskins · Cheyney · Wilson · Andrews · Munro · Taylor · Breasted · Robinson · Greene · Becker · Bolton · Beard · Dodd · Rostovtzeff · McIlwain · Ford · Larson · Ferguson · Farrand · Thompson · Schlesinger · Neilson · Westermann · Hayes · Fay · Wertenbaker · Latourette · Read · Morison · Schuyler · Randall · Gottschalk · Curti · Thorndike · Perkins · Langer · Webb · Nevins · Bemis · Bridenbaugh · Brinton · Boyd · Lane · Nichols · Holborn · Fairbank · Woodward · Palmer · Potter · Cochran · L White · Hanke · Wright · Morris · Gibson · Bouwsma · Franklin · Pinkney · Bailyn · Craig · Curtin · Link · McNeill · Degler · Davis · Iriye · Harlan · Herlihy · Leuchtenburg · Wakeman · Tilly · Holt · Coatsworth · Bynum · Appleby · Miller · Darnton · Foner · Louis · Hunt · McPherson · Spence · Sheehan · Kerber · Weinstein · Spiegel

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

the economic basis of politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

The method of economic interpretation is irrevocably identified with the name of Charles A. Beard, mainly due to An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913). Yet, it is Beard's later work, The Economic Basis of Politics (1922), where he articulates the main principles of his method. In this brief survey of Western political philosophy and contemporary constitutional arrangements, Beard concludes that it is well established doctrine that "there is a vital relation between the forms of state and the distribution of property, revolutions in the state being usually the results of contests over property." --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

the economic basis of politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

The method of economic interpretation is irrevocably identified with the name of Charles A. Beard, mainly due to An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913). Yet, it is Beard's later work, The Economic Basis of Politics (1922), where he articulates the main principles of his method. In this brief survey of Western political philosophy and contemporary constitutional arrangements, Beard concludes that it is well established doctrine that "there is a vital relation between the forms of state and the distribution of property, revolutions in the state being usually the results of contests over property." --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

readings in american government and politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Originally published in 1909. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

our old world background

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

cross currents in europe to day

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: IV THE ECONOMIC OUTCOME OF THE WAR FOR many years before the Great War, the statesmen and diplomats of Europe pursued, let us say patriotically and honorably, the interests of their respective nations as they were given to see those interests. To accomplish their purposes, they relied upon secret negotiations, alliances, ententes, conversations, and understandings and upon huge military and naval equipments. There were some critics who protested against these methods and these reliances, but the statesmen and diplomats were above all things practical men. Their ways were old and tried while all new ways were the ways of visionaries. The practical men had their day. The Great War and its results are the- full fruit of their planting and their cultivating. The present state of Europe is a tribute to their powers of divination and to their genius for the instant need of things. There is no doubt about the present state of Europe. Every day news, every book, every article dealing with Europe bears witness to the chaos that has followed the armistice. Statistical tables that will not be denied tell of staggering debts,mounting deficits, paralyzed industries, inflated currencies, and growing bitterness. At the end of four years of peace, Europe is, in many respects, in a worse condition than at the end of four years of war. Conference after conference has been held and the assembly of the League of Nations has con' vened, but these things have not brought health or understanding. In the midst of gathering difficulties statesmen are frantically talking about "restoring the economic order of Europe," "getting back to normal conditions," and "re-establishing prosperity." This is uppermost now in the minds of leaders like Mr. Lloyd George who, weary of the snarling voices of the O...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

contemporary american history 1877 1913

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1914. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

an introduction to the english historians

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER III ADOPTION OF CHRISTIANITY AND UNIFICATION OF ENGLAND Whatever may have been the nature of the Anglo-Saxon conquest and settlement, the immediate political result was the foundation of several petty tribal states among which there ensued three centuries of warfare for supremacy. Dull as the annals of these three hundred years are, the period was nevertheless one of great importance in the building of the English nation. The heathen conquerors were converted to Christianity, Britain was brought into close relations with Rome, a well- planned ecclesiastical system was founded, monks began there the work of civilization, the arts of peace flourished in spite of the conflicts, and learning increased. Doubtless the most vivid and interesting account of this period is to be found in John Richard Green's Short History of the English People. § 1. Rise of Kent and Landing of Augustine1 The conquest of the bulk of Britain was now complete (ca. 588). Eastward of a line which may be roughly drawn along the moorlands of Northumberland and Yorkshire, through Derbyshire and skirting the Forest of Arden to the mouth of the Severn, and thence by Mendip to the sea, the island had passed into English hands. From this time the character of the English conquest of Britain was wholly changed. The older wars of extermination came to an end, and as the invasion pushed westward in later times the Britons were no longer wholly driven from the soil, but mingled with their conquerors. A far more important change was that which was seen in the attitude of the English conquerors from this time toward each other. Freed to a great extent from the common pressure of the war against the Britons, their energiesturned to combats with one another, to a long struggle for over- lordship which was ... --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

american government and politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1914. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

american citizenship

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Originally published in 1914. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Beard Charles Austin’s History of the United States is a textbook about the American history from its founding to the XIX century. The author explains the historical processes and facts that are reciprocal according to the law of cause and effect. The main advantage of the book is that history isn’t just narrated chronologically but arranged thematically, mostly paying attention to the social and economic aspects as the dominant determinants but not war strategy. Besides the inner historical developments there are described the relations with other countries, the most important of which are ones with Europe.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Beard Charles Austin try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Beard Charles Austin try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!