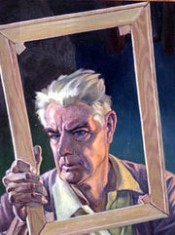

Baldridge Cyrus Leroy

Cyrus Leroy Baldridge (1889 – 1977) was an artist, illustrator, author and adventurer. He was born to a wealthy ne’er-do-well and Eliza Burgdorf Baldridge, in Alton, Illinois in 1889. When very young, his mother left his abusive father and began a nomadic life as a traveling sales person, selling kitchen equipment from town to town. Devoted to this strong and independent woman, Baldridge’s personality absorbed from her a spirit of quite exceptional individualism. Baldridge's career in art began during an extended stay in Chicago, when the 10-year-old Cyrus was accepted as the youngest student of the famous illustrator, Frank Holme. Holme became his second father. In his studio, Baldridge sat with students three times his age to do life drawings of nude models, and under his direction went into the streets to make the quick sketches from life that in those days became newspaper illustrations. He learned to count and remember the number of buttons on a policeman’s jacket, and the sad faces of tenement children, and then return to the studio to include them in finished illustrations. Baldridge was admitted to the University of Chicago in 1907 and graduated in 1911 and was evermore devoted to that institution. He was poor boy with no scholarship in an elite college, and he paid his way by drawing signs for campus events. According to Harry Hansen, "Men who knew him then will talk to you about him by the hour – but not necessarily about his drawings. They will tell you about his honesty, his candor, his sense of democracy, his unfailing good humor and his faith in his fellow man." So much was his popularity that he led his classmates as Grand Marshall of the University when they marched to graduation in 1911. After college, life for Baldridge was a struggle for money but also an exuberant adventure. While looking for commissions as an illustrator, he worked in a settlement house and became an expert rider in the Illinois National Guard Cavalry. Of a summer, he worked as a cow hand on the King ranch in Texas, and as a member of the Cavalry he went to New Mexico during the raids of Poncho Villa. When World War I began, an idealistic Baldridge joined the French army as an ambulance driver. In 1917, his country’s entrance in the War meant his transfer to the American infantry where he was put on the talented team creating the Stars and Stripes newspaper. The staff included Harold Ross, who was to be founder and legendary editor of The New Yorker; Alexander Wolcott, later drama critic for the New York Times and the New Yorker; and Baldridge. In charge of illustration for the magazine, Baldridge traveled freely over the battlefields and was deeply moved by its horror. Baldridge's reputation was launched in the United States when his drawings appeared on many covers of Leslie's Weekly and Scribners during the war years. Near the end of the War, he published his first book, I was There with the Yanks in France. I Was There is a collection of sketches that record, better than cameras could, intimate moments of sadness, heroism and relaxation. Near the time of the book’s publication he told Harry Hansen, "If only I can make the public see what war is – what a dirty, low thing it is, and how brutal it makes men, fine clean men – the they’d fight to the last ditch for the League of Nations." After the war, Baldridge joined his life to that of the writer Caroline Singer. Setting up house in Greenwich Village, they became favorites in the artistic/intellectual circles of New York but followed their own unusual star. With almost no money, they left New York time after time on immense journeys of discovery. To understand better the background of the Negro in America, they traveled, mostly on foot, across Africa from Gold Coast to Ethiopia. Along the way they lived in native villages where Baldridge sketched and communicated with the Africans through pictures. They avoided contact with Europeans, and took no advantage of the special treatment then expected by members of their race. From this journey came a marvelous book, written by Caroline Singer and lavishly illustrated by Cyrus Baldridge, White Africans and Black. It is an elegant and respectful portrayal of black African culture written at a time when whites hardly even acknowledged its existence. The experience left them deeply committed to the rights of black Americans. Baldridge beautifully illustrated several books by African American authors. A set of splendid sketches from his African journey are now part of the collection of Fisk University. Having seen the world and its people at close hand, Baldridge was intense in his refusal to work with any author who portrayed another race as inferior or foolish. More journeys followed to Asia and the Middle East, with other fine books growing out of them. Baldridge and Singer together wrote A Turn to the East, All the World is Isfahan and two children’s books, Boomba Lives in Africa and Ali lives in Iran. In addition, the knowledge he gained of customs and styles in the East brought Baldridge commissions to illustrate many books with oriental motifs. The foremost of these were the stunning 1937 reissue of Hajji Baba of Isfahan by James Morier and the 1941 Translations from the Chinese by Arthur Waley. Both books were early Book-of-the-Month Club special editions and their illustrations, distributed separately by B.O.M.C., were framed and hung on walls in thousands of homes. Cyrus Baldridge was not only an artist but a deeply committed citizen. Disillusion following World War I made him a devoted pacifist and this lasted until Pearl Harbor. He was a socialist and friend and supporter of Norman Thomas. As Caroline Singer became an increasingly important journalist with the New York Times, the New Yorker and others, her articles on the world scene, often illustrated with his drawings, gave voice to their mutual, fervent internationalism. During the Depression, as president of the National Association of Commercial Arts, he was a leader in organizing commercial artists for better pay. In the early 1930s, Baldridge and a group of New York friends organized the Williard Straight American Legion Post to combat the dominant right-wing ideology of the Legion at that time. In fact, of all his work Baldridge was proudest of a small booklet he wrote and illustrated for the Legion called Americanism: What is It. Released in 1936, the booklet was a simple restatement of American values, mostly quoted from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Temporarily accepted as a statement of Legion principle, it was distributed to thousands of schoolrooms until the Legion's right wing noticed and forced its withdrawal. In the 1940s, Cyrus Baldridge illustrated many books and magazine articles and, in 1947, he wrote an autobiography: Time and Chance. The book is both splendidly written and lavishly illustrated. It was well received and went into a number of printings. Profits from Time and Chance, combined with several years of earnings from well-paid work with the Information Please Almanac, made it possible for him and Caroline to retire to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1951. There they lived simply in a small adobe house among like-minded free-spirits. In Santa Fe, Baldridge began to seriously work in oils. His painting ranged over every possible theme, but chiefly portrayed New Mexican landscapes. In the thirty years between his retirement and his death, he hiked virtually the whole of northern New Mexico, sketching with charcoal or water colors, and returning home to complete his work in oils. A large number of these later works are in the collection of the University of Wyoming. The plan of the couple had been for Caroline to write while Cyrus painted during their years of "retirement", but from the time they arrived in New Mexico she suffered from a block to the great abilities that made her so successful in New York. She wrote hardly anything and completed nothing. Later it was speculated that she had begun a series of small strokes that eventually led to dementia and death. Caroline Singer died in 1962. Cyrus Baldridge remained incredibly active and vigorous, full of stories and opinions, until decline began in the mid-1970’s. In 1977, he felt himself losing the battle against age. On the afternoon of June 6, 1977, he committed suicide with a pistol he had been issued in World War I. The bulk of his estate was left to the University of Chicago.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

"I was there" with the Yanks on the western front, 1917-1919

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

"I was there" with the Yanks on the western front, 1917-1919

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Baldridge Cyrus Leroy try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Baldridge Cyrus Leroy try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!