28 Oct 2011 08:29:04

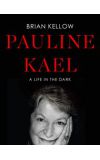

"Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark" (Viking), by Brian Kellow: Film critic Pauline Kael could be as brilliant and maddening in person as she was in the pages of The New Yorker, whether you were a filmmaker who failed to meet her standards or an acolyte who dared to disagree with her judgment.

Movies, after all, were her life.

Some considered Kael an irresponsible bully and an opportunistic writer who could be far too chummy with filmmakers. Others found her friendly, gregarious and bawdy, though hardly faultless, sometimes boorish but never boring. She reveled in such attention and devoted herself to earning it.

In "Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark," author Brian Kellow offers a making-of story as engaging as her criticism. It's no easy feat — what's less dramatic than scribbling into the night? — but Kellow tapped her friends and foes and her writing while developing a colorful, evenhanded appreciation of one of film's most influential critics.

Her first movie review appeared in 1952. Kael was 33, a single woman in San Francisco struggling to raise an out-of-wedlock daughter and getting nowhere in a series of jobs and with her fiction writing. Marrying the owner of a repertory theater would give her a reliable platform to write about film, even if only for programming notes. The arrangement appeared more about Kael gaining financial traction than love.

Similar decisions by Kael focused on getting ahead. Writing bold essays taking a contrarian view was one strategy; attacking fellow critics was another. At times she was accused of getting her facts wrong and faking a technical or business knowledge of filmmaking to make a point. She apparently based her controversial 1971 essay on "Citizen Kane" on research she failed to credit — "stole" might be the proper word.

A literate style driven by passionate opinions and punctuated with cutting, crude remarks was central to her appeal. (Director Billy Wilder's comedy "One, Two, Three," she wrote, "pulls out laughs the way a catheter draws urine.") She could overly praise movies, too, like "Last Tango in Paris" ("a landmark in movie history"), and she practically wet-nursed directors like Robert Altman and Brian De Palma when she believed they were misunderstood by other critics or abused by the studios.

Reading about Kael — she retired as a regular reviewer in 1991 and died in 2001 — will no doubt rekindle interest in her work. Right on cue comes "The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael" (Library of America). It's a grand collection of her more challenging, provocative and argument-inducing views, and a perfect companion to Kellow's eye-opening biography.