20 Oct 2011 09:41:25

In the last year of Ian Fleming's life – 1964 – he often watched Sussex play cricket at Hove in the company of Alan Ross, editor of London Magazine. In Ross's wonderful memoir, Coastwise Lights, he has this to say about the creator of James Bond: "Ian's idea of giving up smoking on doctor's orders was to cut down from sixty a day to thirty … and on instruction he reduced his intake of Vodka Martini from three lethal doses to one. He was very shaky, his normally brick-red complexion the dry mauve of a paper flower." Fleming was 56 and indifferent about living longer. He once revealingly described his own character thus: "I've always had one foot not wanting to leave the cradle and the other in a hurry to get to the grave." This strange mixture of the infantile and the world-weary seems very typical of the man. A few months earlier he had been visited by Evelyn Waugh. Waugh was a friend of Fleming's glamorously waspish wife Ann and didn't like Fleming much. The feeling was mutual. Waugh wrote to Nancy Mitford: "[Ian] looks and speaks as though he may drop dead any minute. His medical advisors confirm the apprehension."Where did this implicit death wish come from? In some ways it's a very English slow suicide – one that Waugh, incidentally, was also participating in – obesity, cigars, alcohol and assorted drugs hastening him to an early grave two years after Fleming. Yet, on paper, Fleming had everything to live for. Born into a rich and well-connected Scottish banking family, he went to Eton, briefly to Sandhurst and then became a remittance man, notionally working in the City – "the world's worst stockbroker", in his own estimation – enjoying pretty girlfriends, fast cars and foreign holidays. After the war, during a spell at the Sunday Times, he began to write the James Bond novels, one a year from 1953 to his death. To new global fame could be added even more riches. Why was he so unhappy?

It's hard to explain this taedium vitae when it seems that most of life's injustices, hassles and difficulties – large and small – have been erased by wealth. My own feeling is that Fleming couldn't get over the second world war. As for many of his generation the war was both a gigantic upheaval and an astonishing adventure in his life, an unparalleled episode in which he had found himself and felt his work had been both meaningful and useful. In other words, during the war, paradoxically, he had been happy. When it was over the meaninglessness of his feather-bedded existence slowly re-established itself.

Fleming's good fortune was to be recruited in 1939 into the Naval Intelligence Division as personal assistant to NID's head, Admiral John Godfrey. He had a rank in the RNVR – commander – wore a uniform and went to work in the Admiralty. Everything about his life had changed. As a result of this key role and position he not only was connected to the very centre of the secret world of spies and spying but he could also actively participate in it – travelling to France and Spain, the US and Canada – suggesting ideas and schemes as they came to him, some of which were taken up and provided notable covert successes.

The most remarkable and lasting of these was his suggestion that a special commando be set up – a small group of intelligence-gathering raiders – who would attack and plunder targeted German establishments – radar stations, Kriegsmarine offices, naval installations and the like – and "pinch" anything that that might be useful – code books, movement orders, bits of Enigma machines and so forth. The force that was established as a result of Fleming's brainwave was called the 30 Assault Unit, a commando that saw its first operation during the disastrous 1942 raid on Dieppe. Fleming was on board a destroyer not far from the beaches during the raid and it was not an auspicious start, as even he had to admit, but 30AU was to prove itself invaluable in north Africa, Sicily, Italy, Rhodes, Yugoslavia, the invasion of France – and, most effectively, in Germany during the final days of the Third Reich when, among the wholesale larceny of German technology that was taking place as the war ended, its most audacious "pinch" of all was achieved, namely, the entire archive of the German Navy – the Tambach Archives, a vast document haul that weighed more than 400 tons.

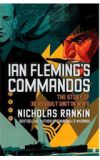

Nicholas Rankin's fascinating book is an account of the 30AU's progress through the war. From time to time it reads like a Boy's Own story, so flamboyant are the characters and so vivid Rankin's accounts of the deadly scrapes and firefights the commandos found themselves involved in. The research is prodigious and lucid – now I finally understand how an Enigma machine works – and one gains a real sense of how these maverick units functioned, very much akin to the Long Range Desert Group and the fledgling SAS.

As well as being intrepid fighters it seemed as much a requisite of joining 30AU that the soldiers possessed strong, not to say eccentric, personalities. Rankin describes these extraordinary men – Bon Royle, Lofty Whyman, Patrick Dalzel-Job, "Sancho" Glanville and Peter Huntington-Whitely among others – and details their audacious exploits from 1942 onwards; he demonstrates how many of 30AU's pinches facilitated the code-breakers of Bletchley Park. Captured Enigma machines, cipher books and coded messages were sent back for analysis and, as the code-breakers grew ever more efficient at their work, it is clear that Fleming's commandos actively aided the general war effort and possibly shortened the conflict.

The commandos were unaware of the actual contribution and long-term effects of their looting – as, probably, was Fleming. He remains something of a background figure in the account, occasionally visiting the men on the front line (and complaining about the quality of the brandy he was served) and not much loved, it has to be said. This again is probably a result of a particular trait of the privileged English classes. Fleming found it hard to mix with others outside his own society and to express emotion, like many of his peers, and cultivated instead the very English phenomenon that Rankin calls "the façade of nonchalance".