24 Aug 2010 11:01:16

In our days there are a lot of people who have got problems with grammar in English. That is why two young Americans took it upon themselves to correct public typos during a three-month road trip across the country. They have written about the trip in a book that exposes deficits in both public education and attention to detail.

"The Great Typo Hunt" describes a nationwide mission by Jeff Deck and Benjamin D. Herson, both 30, to rid America of signs that add an extra "n" to "dining", or insist that "shipping" is spelled with one "p".

Deck, a magazine editor, and Herson, a bookseller, drove across the country in the spring of 2008 armed with sharpies, pens and whiteout, correcting spelling, removing surplus apostrophes and untangling subject-verb disagreement on signs outside stores, gas stations, parks and public buildings.

Calling themselves the Typo Eradication Advancement League, they found hundreds of signs indicating the writers either didn't know or didn't care that their spelling, grammar, or punctuation was wrong, and were apparently unaware that their mistakes risked exposing them to public derision or, worse, misunderstanding.

In Atlanta, they found a sign advertising both a "pregnacy" test and a "souviner" of the city to remind tourists of their visit.

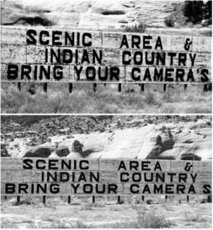

In Arizona, a placard urging tourists to bring their "camera's" prompted Deck and Herson to remove the gratuitous apostrophe, leaving the sign with a gap that was at least less offensive than what it replaced.

Sensitive to the charge of being overzealous pedants, they argue that public typos are about more than just a few misplaced punctuation marks. Such errors may lead the reader to get a poor impression of the writer in general, they argue.

"If you put a bunch of typos out for the world to see, people might draw conclusions about attention to detail in other matters," Deck said in an interview.

When they found public typos, Deck and Herson were careful to seek the permission of the signs' owners to make the needed changes.

Around 60 percent took a defensive posture and declined any typo services, notably two people who threatened the pair when they were about to fix a sign on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. They were warned to "keep walking or they would make sure we didn't walk again," Deck said.

They also ran into trouble at the Grand Canyon where they were arrested for fixing bad grammar in an official sign. A federal judge fined them $3,000 and banned them from speaking publicly about fixing typos for a year, a period that expired in August 2009.

A prosecutor's press release about the Grand Canyon case called them "self-proclaimed grammar vigilantes", a label that was echoed in media reports but which Deck and Herson reject, arguing that they take a "kinder, gentler" approach to grammar that doesn't blame anyone for mistakes.

"We are not angry grammarians," Deck said.

While typographical errors have been the source of sarcasm from some high-minded individuals, Deck and Herson set out to show people the error of their ways rather than just complaining about it, he said.

Their approach was appreciated by a Seattle maker of "dillettante chocolate" who graciously accepted their observation that his "dilettante" had one too many 'l"s.

"The Great Typo Hunt" describes a nationwide mission by Jeff Deck and Benjamin D. Herson, both 30, to rid America of signs that add an extra "n" to "dining", or insist that "shipping" is spelled with one "p".

Deck, a magazine editor, and Herson, a bookseller, drove across the country in the spring of 2008 armed with sharpies, pens and whiteout, correcting spelling, removing surplus apostrophes and untangling subject-verb disagreement on signs outside stores, gas stations, parks and public buildings.

Calling themselves the Typo Eradication Advancement League, they found hundreds of signs indicating the writers either didn't know or didn't care that their spelling, grammar, or punctuation was wrong, and were apparently unaware that their mistakes risked exposing them to public derision or, worse, misunderstanding.

In Atlanta, they found a sign advertising both a "pregnacy" test and a "souviner" of the city to remind tourists of their visit.

In Arizona, a placard urging tourists to bring their "camera's" prompted Deck and Herson to remove the gratuitous apostrophe, leaving the sign with a gap that was at least less offensive than what it replaced.

Sensitive to the charge of being overzealous pedants, they argue that public typos are about more than just a few misplaced punctuation marks. Such errors may lead the reader to get a poor impression of the writer in general, they argue.

"If you put a bunch of typos out for the world to see, people might draw conclusions about attention to detail in other matters," Deck said in an interview.

When they found public typos, Deck and Herson were careful to seek the permission of the signs' owners to make the needed changes.

Around 60 percent took a defensive posture and declined any typo services, notably two people who threatened the pair when they were about to fix a sign on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. They were warned to "keep walking or they would make sure we didn't walk again," Deck said.

They also ran into trouble at the Grand Canyon where they were arrested for fixing bad grammar in an official sign. A federal judge fined them $3,000 and banned them from speaking publicly about fixing typos for a year, a period that expired in August 2009.

A prosecutor's press release about the Grand Canyon case called them "self-proclaimed grammar vigilantes", a label that was echoed in media reports but which Deck and Herson reject, arguing that they take a "kinder, gentler" approach to grammar that doesn't blame anyone for mistakes.

"We are not angry grammarians," Deck said.

While typographical errors have been the source of sarcasm from some high-minded individuals, Deck and Herson set out to show people the error of their ways rather than just complaining about it, he said.

Their approach was appreciated by a Seattle maker of "dillettante chocolate" who graciously accepted their observation that his "dilettante" had one too many 'l"s.