21 Aug 2010 14:57:17

My first trip to Moscow was at the time when in Russia was socialism. All people tried to live with the Lenin's famous phrase "Socialism plus electrification equals communism". The slogan encapsulated several central aspects of communist thought. First, optimism for the future. Second, that science and technology were both by definition progressive forces but were impeded by capitalism; only under communism could they enable the building of a society of abundance for the many, not just the few.

At that time it was veru popular the Marxist doctrine. When Friedrich Engels's fragmentary text, The Dialectics of Nature, dating from 1883, was rediscovered in the 1930s, it was regarded as demonstrating that nature itself conformed to the philosophical principles that he and Marx had formulated in their decades of collaboration. Then in 1948 the American mathematician Norbert Wiener published his path-breaking book (and invented the word itself) Cybernetics, a way of thinking about how self-regulating systems interact dynamically with their environment, both changing it and being changed by it. Cybernetics ("circular causation") was a way of understanding how systems could show apparent goal-directed behaviour without consciousness. Soviet philosophers seized on the concept, elevating it to the status of a "fourth law of dialectics".

Following Stalin's death and the slow thaw, initiated by Khrushchev, that lasted from the mid-1950s to the mid-60s, Soviet planners, economists, physicists and mathematicians flourished. They persuaded the Soviet leadership that, using cybernetic principles and the newly developed computers, the centralised, planned Soviet economy could at last be made efficient. By 1980, Khrushchev claimed, the Soviet Union would overtake America; communism would have defeated capitalism. For a while, in the aftermath of Sputnik and Gagarin's space flight, it looked as if he might be just be right.

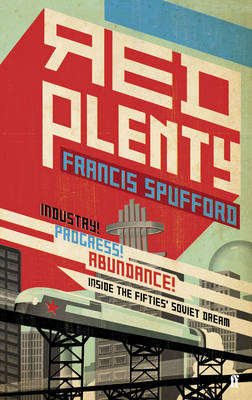

So what went wrong? It is this question that Francis Spufford explores in Red Plenty. Not as history, nor yet exactly as a novel, but in a series of loosely linked chapters, each a vignette in which fictional characters rub shoulders with real ones. The cast list at the front distinguishes real from invented, although two of the latter, as Spufford makes clear, are "stand-ins" for the real economist Abel Aganbegyan and the molecular geneticist Raissa Berg (the latter still alive at last count and now resident in the US). The key real figures are the mathematical prodigy and later Nobelist Leonid Kantorovich, whose initial calculations on how to improve plywood production blossomed into a comprehensive plan for the economy, and Sergei Lebedev, designer of the first generations of Soviet computers.

But could it have worked? Can we ever once more believe that we, the people, could create a just, equal and abundant society? Red Plentyends with the question that must carry all our hopes and fears, as Khrushchev, the deposed pensioner, broods: "Years pass. The Soviet Union falls. The dance of commodities resumes. And the wind in the trees of Akademgorodok says: can it be otherwise? Can it be, can it be, can it ever be otherwise?"

At that time it was veru popular the Marxist doctrine. When Friedrich Engels's fragmentary text, The Dialectics of Nature, dating from 1883, was rediscovered in the 1930s, it was regarded as demonstrating that nature itself conformed to the philosophical principles that he and Marx had formulated in their decades of collaboration. Then in 1948 the American mathematician Norbert Wiener published his path-breaking book (and invented the word itself) Cybernetics, a way of thinking about how self-regulating systems interact dynamically with their environment, both changing it and being changed by it. Cybernetics ("circular causation") was a way of understanding how systems could show apparent goal-directed behaviour without consciousness. Soviet philosophers seized on the concept, elevating it to the status of a "fourth law of dialectics".

Following Stalin's death and the slow thaw, initiated by Khrushchev, that lasted from the mid-1950s to the mid-60s, Soviet planners, economists, physicists and mathematicians flourished. They persuaded the Soviet leadership that, using cybernetic principles and the newly developed computers, the centralised, planned Soviet economy could at last be made efficient. By 1980, Khrushchev claimed, the Soviet Union would overtake America; communism would have defeated capitalism. For a while, in the aftermath of Sputnik and Gagarin's space flight, it looked as if he might be just be right.

So what went wrong? It is this question that Francis Spufford explores in Red Plenty. Not as history, nor yet exactly as a novel, but in a series of loosely linked chapters, each a vignette in which fictional characters rub shoulders with real ones. The cast list at the front distinguishes real from invented, although two of the latter, as Spufford makes clear, are "stand-ins" for the real economist Abel Aganbegyan and the molecular geneticist Raissa Berg (the latter still alive at last count and now resident in the US). The key real figures are the mathematical prodigy and later Nobelist Leonid Kantorovich, whose initial calculations on how to improve plywood production blossomed into a comprehensive plan for the economy, and Sergei Lebedev, designer of the first generations of Soviet computers.

But could it have worked? Can we ever once more believe that we, the people, could create a just, equal and abundant society? Red Plentyends with the question that must carry all our hopes and fears, as Khrushchev, the deposed pensioner, broods: "Years pass. The Soviet Union falls. The dance of commodities resumes. And the wind in the trees of Akademgorodok says: can it be otherwise? Can it be, can it be, can it ever be otherwise?"