21 Feb 2011 13:54:12

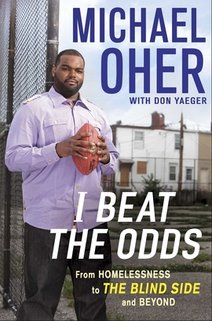

It is a new book from legendaries Don Yaeger and Michael Oher. This book become the best-seller for very short period and won the hearts of many strict people.

While there's some inevitable retread here — Lewis is, after all, one of the finest journalists of his generation — there's much to be gained from hearing the story straight from the man dubbed "Big Mike." His own voice is matter-of-fact, both hopeful and a touch melancholy.

His experience growing up poor in Memphis, Tenn., was, if anything, more harrowing than it was portrayed in the film. He saw a baby shot by a stray bullet, struggled to find meals, and his mother's on-again, off-again relationship with drugs nearly prevented him from reaching his potential.

"My mother did her best," Oher writes. "I have to give her that much. When she was sober, she worked hard to give us a good home and look after us. The problem was that she was not sober very much."

There are other interesting rejoinders to Hollywood's version of Oher's life. He was not, as portrayed, an untrained rube on the football field; he was already quite good. Photos in the book show that while Bullock might have been a deadringer for Oher's adoptive mother, Leigh AnneTuohy, Tim McGraw was a flattering choice to play Sean Tuohy, Oher's adoptive father. And so on.

In telling his side of "The Blind Side," Oher's prose is not always as purple as his No. 74 Baltimore Ravens jersey. One chapter begins with a stretched reference to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. That said, the sports biography genre is not one particularly well-known for its literary pizazz. This book also moves along at a brisker pace than your average NFL game.

Where "Odds" succeeds most is in going beyond what we have seen — overglossed as it may have been — and into an assessment of life after your life story is put on the big screen. What Oher describes is a strange, disorienting experience for a man already living the typically surreal existence of a professional football player.

Oher is genuinely awed by the impact of his story. He is baffled at how it makes some people teary.

But he also obviously takes pride in the effect telling his story has had on others. He writes about the piles of letters he receives each day and comes to a conclusion that offers both a sad coda and something of a call to action: "What these letters tell me is that kids like me aren't the exception. There are a lot of us whose ... struggles sound familiar."

While there's some inevitable retread here — Lewis is, after all, one of the finest journalists of his generation — there's much to be gained from hearing the story straight from the man dubbed "Big Mike." His own voice is matter-of-fact, both hopeful and a touch melancholy.

His experience growing up poor in Memphis, Tenn., was, if anything, more harrowing than it was portrayed in the film. He saw a baby shot by a stray bullet, struggled to find meals, and his mother's on-again, off-again relationship with drugs nearly prevented him from reaching his potential.

"My mother did her best," Oher writes. "I have to give her that much. When she was sober, she worked hard to give us a good home and look after us. The problem was that she was not sober very much."

There are other interesting rejoinders to Hollywood's version of Oher's life. He was not, as portrayed, an untrained rube on the football field; he was already quite good. Photos in the book show that while Bullock might have been a deadringer for Oher's adoptive mother, Leigh AnneTuohy, Tim McGraw was a flattering choice to play Sean Tuohy, Oher's adoptive father. And so on.

In telling his side of "The Blind Side," Oher's prose is not always as purple as his No. 74 Baltimore Ravens jersey. One chapter begins with a stretched reference to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. That said, the sports biography genre is not one particularly well-known for its literary pizazz. This book also moves along at a brisker pace than your average NFL game.

Where "Odds" succeeds most is in going beyond what we have seen — overglossed as it may have been — and into an assessment of life after your life story is put on the big screen. What Oher describes is a strange, disorienting experience for a man already living the typically surreal existence of a professional football player.

Oher is genuinely awed by the impact of his story. He is baffled at how it makes some people teary.

But he also obviously takes pride in the effect telling his story has had on others. He writes about the piles of letters he receives each day and comes to a conclusion that offers both a sad coda and something of a call to action: "What these letters tell me is that kids like me aren't the exception. There are a lot of us whose ... struggles sound familiar."