20 Oct 2010 13:54:51

Germany's surrender, in the midst of a victors' summit, war-weary British voters threw him out of office.

Churchill had effectively lost his top status in the final weeks of the war. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American commander of Western forces marching on Berlin, gave up the race against Soviet troops advancing on the city from the other direction.

Churchill had begged Roosevelt to make Eisenhower capture Berlin, pleading in vain that a Soviet victory would give Stalin too much influence in postwar Europe. Churchill liked to say that if his advice on Germany had been taken in the 1930s, there might have been no need for World War II. Out of power for six years after his election defeat, he kept urging a settlement with the Soviets while the United States still had a monopoly on the atomic bomb.

His famous "Iron Curtain" speech in 1946 warned against Soviet expansionism and urged the special relationship between Britain andAmerica.

Though the Soviets accused him of warmongering and there was much controversy over the speech, his views on the Soviets were much like those of America's leaders. President Harry S. Truman — who had invited him to speak — sat on the platform, applauded and wrote his mother that he wouldn't endorse the speech but it might do some good.

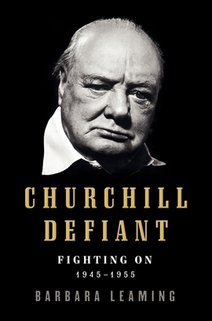

"...(T)here was perhaps little room to quarrel with Churchill's blunt review of unpleasant facts," biographer Barbara Leaming writes in "Churchill Defiant." It's a sympathetic and highly readable account of his last decade as an active politician.

Leaming takes the reader on an intimate cruise of British politics: the intrigues of cabinet government and the importance of the royal prerogative, as exercised by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II.

Though the royals are supposed to keep out of politics, Churchill gave great importance to consultations with them. The book also explores the ins and outs of the special relationship with Washington, including the disquiet among British leaders over suggestions that Eisenhower might use nuclear weapons against China in the Korean War.

His aim throughout: Keep Britain part of the Big Three, on equal footing with the United States and the Soviet Union. But neither Truman nor Eisenhower, his successor, accepted that. Britain, weakened by two world wars, was leaning on American aid and losing its empire; India was already an independent republic.

Churchill fought two more elections, winning reinstatement as prime minister after the second. In his mid-1950s, he found leaders of his Conservative Party, including his designated successor, Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, intriguing against him while outwardly supportive.

Churchill was in bad shape physically, suffering from one stroke and fearing another, increasingly deaf, nodding off at meetings. But he repeatedly refused to resign.

Churchill had effectively lost his top status in the final weeks of the war. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American commander of Western forces marching on Berlin, gave up the race against Soviet troops advancing on the city from the other direction.

Churchill had begged Roosevelt to make Eisenhower capture Berlin, pleading in vain that a Soviet victory would give Stalin too much influence in postwar Europe. Churchill liked to say that if his advice on Germany had been taken in the 1930s, there might have been no need for World War II. Out of power for six years after his election defeat, he kept urging a settlement with the Soviets while the United States still had a monopoly on the atomic bomb.

His famous "Iron Curtain" speech in 1946 warned against Soviet expansionism and urged the special relationship between Britain andAmerica.

Though the Soviets accused him of warmongering and there was much controversy over the speech, his views on the Soviets were much like those of America's leaders. President Harry S. Truman — who had invited him to speak — sat on the platform, applauded and wrote his mother that he wouldn't endorse the speech but it might do some good.

"...(T)here was perhaps little room to quarrel with Churchill's blunt review of unpleasant facts," biographer Barbara Leaming writes in "Churchill Defiant." It's a sympathetic and highly readable account of his last decade as an active politician.

Leaming takes the reader on an intimate cruise of British politics: the intrigues of cabinet government and the importance of the royal prerogative, as exercised by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II.

Though the royals are supposed to keep out of politics, Churchill gave great importance to consultations with them. The book also explores the ins and outs of the special relationship with Washington, including the disquiet among British leaders over suggestions that Eisenhower might use nuclear weapons against China in the Korean War.

His aim throughout: Keep Britain part of the Big Three, on equal footing with the United States and the Soviet Union. But neither Truman nor Eisenhower, his successor, accepted that. Britain, weakened by two world wars, was leaning on American aid and losing its empire; India was already an independent republic.

Churchill fought two more elections, winning reinstatement as prime minister after the second. In his mid-1950s, he found leaders of his Conservative Party, including his designated successor, Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, intriguing against him while outwardly supportive.

Churchill was in bad shape physically, suffering from one stroke and fearing another, increasingly deaf, nodding off at meetings. But he repeatedly refused to resign.