19 Jan 2014 17:35:09

By 2017, according to the Solving the E-Waste Problem (Step) initiative, a UN-supported project, each person on the planet will discard a third more electronic waste than in 2012, a grand total by then of 64.4m tonnes. Much of it will be shipped from the affluent world to developing countries for cheap reprocessing, a pattern of trade that Step defines as a problem. Adam Minter, a journalist and son of a US scrapyard entrepreneur, would disagree. Minter does not see the global scrap trade as a morality tale of villain and victim, but a vibrant and eco-friendly business, a core component of the world economy.Most people want to throw away and forget, saving their excitement for the new. What happens to the waste we discard is banished to society's margins. People with better options, as Minter acknowledges, do not go into waste processing: it is an outsider's profession, the first step on the ladder for recent arrivals, people with few marketable skills, or those excluded by prejudice from other professions. In the US, the largest group in the business is Jewish, like the Minter family.

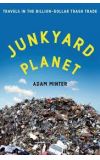

Minter's accomplishment is to take his reader through the secret gate into this teeming world of giant machines, self-made millionaires and barefoot rag pickers, all in different ways tenacious entrepreneurs in a business that is worth $500bn a year. Junkyard Planet is a gripping odyssey around the world's rubbish mountains and the men and (occasionally) women who mine them and turn them into money.

Adam Minter is an intimate of the junk world's trade fairs and global networks and a wholehearted evangelist for junk. It is a passion born between eating kosher hotdogs with his grandmother in the family junkyard in Minneapolis, and one that compels him to seek out and visit junkyards even while on holiday. (His wife merits a sympathetic aside here.) Minter loves it: the giant car crushers and ingenious conveyor belts that progressively separate out components; the rag pickers sorting different colours of plastic in a shed in China; the complexities of the trade's taxonomy and its terms of art, terms such as mill scale (a steelmaking residue), Barley (clean wire), Talk (aluminium copper radiators) – shorthand terms for scrap's infinite varieties.

Statistics tumble out: the global trade in junk is the biggest employer on the planet after agriculture, a high-volume, low-margin business in which success depends on an ability to recognise the precise ratios of trash components, understand how to separate them and to know where the customers are. In the US, its economics depend on technology; elsewhere, on low wages.

The town of Shijiao in China's Guangdong province is entering its busy season: that is because it is the world centre of discarded Christmas tree lights, processing some 22m pounds of them a year. Shijiao was once a little rural town with nothing to offer the booming Chinese economy but space and cheap labour. Its one strategic advantage was proximity to what was rapidly becoming the world's factory, with its thousands of manufacturing plants hungry for copper. Burning off cable insulation to release the copper required nothing more than a place to do it and a tolerance for dangerous fumes. By the year 2000, 74% of China's demand for copper was fed by scrap.

As the economy grew, demand for plastic also expanded, making recycling the wire insulation also profitable. Today, that component of discarded Christmas tree lights will probably end up as the sole of a pair of slippers. If they had not come to Shijiao, shipped in containers that would otherwise return home empty from delivering China's exports, the lights would have gone to landfill in the United States and elsewhere, and fresh copper mines would be needed to meet the demand. As Minter shows, waste harvesting works not because it is ethical but because it makes money.

Minter's enthusiasm does not blind him to the problems. In the town of Guiyu, for instance, in southern China's unspeakably polluted centre of e-waste, he acknowledges the consequences of irresponsible reprocessing, of workers unprotected from hazardous contaminants and grossly polluted land and water. But he makes a robust case for the trade as a better alternative to more mining or landfill, extracting value at the least cost through ingenuity, expertise and technology.

He meets young men who can tell at a glance how much extractable metal any model of mobile phone contains, or what reusable components a discarded computer contains. They are recent recruits to a profession that made millionaires of men such as Leonard Fritz, who began as a nine-year-old, grubbing in the rubbish dumps of Detroit, pulled off a deal for 3,000 tonnes of mill scale at 15, and built one of the world's largest recycling businesses. Then there is Joe Chen, a Taiwanese American in his early 70s with an encyclopaedic memory for past and present prices, necessary skills in a trade in which a small price moment can mean ruin. Without men like him, we would be neck deep in our own rubbish.