06 Oct 2013 04:17:32

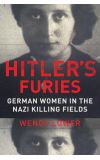

Wendy Lower's book interweaves the experiences of 13 ordinary women who went to work in the East. Aimed at the general reader, it briskly sketches in the position of women in Nazi Germany and then skilfully introduces its cast: the hard-hearted nurse drawn into the euthanasia programme; the idealistic teacher dispatched to Poland; the shepherd's daughter who wants more from her life; the educated woman unable to practise law and drafted into service as a military nurse; the small-town swindler; the pretty 19- year-old eager to avoid a Leipzig car factory; several ambitious secretaries in security police offices; and three women married to SS officers.

The narrative begins in late 1941, with the Final Solution still in its early stages. Jews have been rounded up in ghettoes (which some of the women visit as tourists), Jewish houses and possessions are being taken over and Einsatzkommandos carry out summary executions. The menfolk come back from a long day in the killing fields in need of food, drink and sexual comfort. The teachers, nurses and secretaries are not directly exposed to the Holocaust, but they know it is there. The middle-class nurse hears things from soldier patients and overhears conversations in trains. "People who have no moral inhibitions exude a strange odour," she writes. "I can now pick out these people, and many of them really do smell like blood." Despite her indignation, she stays at her post.

Lower conveys well the physical and moral landscape of this period: how, before the extermination camps were introduced, the atmosphere was permeated by the thousands of hastily buried corpses beneath the ground; how it was all too easy for those with little education and few moral anchors to lose their way in the "Wild East". For some of these women, violence and murder became part of a rich brew of new-found power and sexual arousal – known as Ostrausch or "Eastern rush". Several enjoyed strutting around brandishing whips at Jews; three went beyond posturing and murdered Jewish children.

At this point, there are problems. It isn't just that Lower dwells too much on the horrors; other questions arise. How representative are these women – six of whom turn out to be "perpetrators"? Lower largely ignores professional killers – women in positions of real power in the Reich Security Main Office or the SS – and concentrates on amateurs, whose killing was dictated by simple opportunity, individual character, proximity to power and violent settings, and a wish to emulate their male partners. So why should we want to read about them? Because, Lower argues, they collectively show that the role of women in the Holocaust has been underplayed; obscured by their later stereotypes as heroic "rubble women" clearing up the mess of Germany's past, victims of marauding Red Army rapists, or flirtatious dolls who entertained American GIs.

Lower oversells her material. There is vivid new detail here, but the broad outlines of this story have been around for a while. The role of women under the Nazis has been churned over for the past 30 years; nobody accepts that stuff about Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church) any more. That women, as well as men, can abuse their fellow human beings, is hardly the novelty she claims.