05 Sep 2013 04:23:27

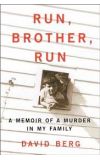

The readers have spoken. The runaway winner of our summer reads readers' choice award is Run, Brother, Run: A Memoir of a Murder in My Family by David Berg with almost half (49%) the votes. As promised we are publishing an extract below. An honorable mention goes to our runner-up, The Good Life Lab by Wendy Tremayne, which got a solid 31%. We hope you have enjoyed reading our selection of newly published book this summer. We will back towards the end of the year with a new batch of Winter Reads. Until then, read on …

Run, Brother Run: A Memoir of Murder in My Family

A month later, Alan disappeared.

Harriet called me at four in the morning.

"David, Alan's not home yet. Do you know where he is?"

"Oh, shit, Harriet. I don't have any idea. I haven't heard from him. Have you?"

"He said he'd made a sale and was meeting Fergis for a drink at the Brass Jug. I was hoping you'd know where he was."

"I don't."

"Oh, God, David, he has never done anything like this. I'm really worried."

"Have you called the police?"

"Do you think I should?"

"I don't know. He'll probably come rolling in the minute you do."

"He better. Maybe your father knows where he is. And Fergis. I'll call them both."

Then Harriet hesitated. "Can you come over? I'm scared."

Dayle was awake now, too. She said to wait and she'd come with me. I walked onto the balcony of our apartment and lit a cigarette. My T-shirt stuck to my skin; the air was oppressive. My stomach jerked.

"Oh, fuck, Alan," I said, "don't do this, don't do this."

The phone rang again. It was my father.

"Alan hasn't come home yet," he said. "Do you know where he is?"

"I don't. I told Harriet that. I haven't heard from him."

"She called you already? I'll be damn. She and I are pretty darn close."

"He told Harriet he'd made a sale. Do you know who to?"

"No. He takes the leads with him."

"Do you know if Harriet's called the police?"

"No. I'm going to call them as soon as we hang up."

"He'll show up soon. He's probably still with Fergis somewhere."

"That bastard better not be with another woman."

That, of course, was exactly where I wanted Alan to be: asleep with another woman, in calamitous trouble with Harriet—as long as he was okay.

Dad and I drove to the Brass Jug, in the heart of Houston's Sin Alley, an area notorious for bars, drugs, and obliging young women that had sprung up so quickly, and in such close proximity to River Oaks and its Church of St. John the Divine—just five minutes away—that it shocked the entire town. And it was there, just across from the entrance to the Brass Jug, that we found Alan's Cadillac, parked and locked. We knocked on the club's door, but no one answered. As we walked back to Dad's car, he said: "This looks bad, doesn't it, son?"

"He'll show up, Dad. He's probably asleep somewhere. You know how late he can sleep. Give him a couple hours and he'll show up."

"What do you think? Do you think he's okay?"

"I don't know, Dad. I just don't know. This isn't like him."

"Should we tell your mother?"

We agreed we shouldn't, not yet. If Alan reappeared of his own accord, she would have suffered for nothing, and if he didn't, well . . . she would call us every five minutes looking for an update, and what good would that do?

After agreeing to come back to the Brass Jug when it opened that evening, I went to Harriet's, and Dad went home. Meanwhile, Harriet had called Fergis, who, assuming Alan had gone off with a woman, tried to cover for him, telling Harriet that he and Alan had had a drink and that he'd left Alan at the table by himself and gone home. But when Dad and I returned to the Brass Jug that evening, no one remembered seeing Alan come or go and we learned nothing. From the club, Dad called the Houston Police Department and was referred to the Homicide Division, where the detective declined to come to the scene, even with Alan's car undisturbed. "Lots of husbands take off without saying good-bye," the detective said. No matter how vehemently Dad insisted that Alan loved his family and would never do that to his wife and kids, the cop dismissed Alan as a runaway husband and refused to open a file.

Three days later, we still had no word from Alan, and still the police refused to act—so my father did. He posted a $5,000 reward, a good chunk of the cash that Dot had been squirreling away over the years since the fire.

The first tip came from a lawyer Dad knew from our synagogue, who said that Alan had been spotted in Chicago and that all he needed to bring him home was $500 and airplane tickets for himself and his private investigator. Ecstatic, Dad gave him what he asked for and told us all that Alan would be back soon. But for seven days and nights there was no word from the attorney, until, finally, he returned, "just heartsick" about what had proven to be "a case of mistaken identity." Sometime later, Dad found out the lawyer had gone to Chicago with his girlfriend.

Then the homicide detective Dad had spoken to on the very first day of Alan's disappearance called to say that he had been thinking about the situation and was concerned about security at Dad's house. Given how little interest the detective had shown in Alan previously, my father interpreted the call as a change of heart and gratefully agreed that the detective and his deputy could come by and check things out. When they arrived—neither man was wearing an officer's uniform, and in fact one of them was not a cop, but a private detective—they sat down with Dad and Dot in the den. When the detective suggested that they move into the kitchen so that his "partner" could check the den and the remainder of the house without distraction, Dot was suspicious and refused to budge, but Dad insisted. Soon after moving into the kitchen, they heard a loud crash. Dot ran into their bedroom and, seeing that a painting had fallen, told the investigator that she didn't have a wall safe, so he could quit looking. Then she kicked them out. Within the month, their house was broken into and all of Dot's jewelry was stolen, including the 2.5-carat diamond ring Dad had given her for our prosperous Christmas fifteen years earlier.

Luckily, Dot recently had parked their remaining savings, about $12,000, in a certificate of deposit with a California savings and loan, where she got a higher interest rate than she could get in Texas. They also had Dad's income from Imperial Carpet, but as he became more and more obsessed with finding Alan, the business fell apart. Sometimes, even in the middle of a carpet pitch, he would bolt to his car, possessed by a need to "look for Alan" around town.

When Alan had failed to call her for a week, Mom knew something was wrong—and Linda told her the truth. After that, hysterical and rambling, Mom called Linda several times a day, and sometimes Dad and me as well, asking whether we were ever going to find her baby. Once or twice she could not resist blaming Alan's disappearance on Dad's "rotten" business, and they'd scream at each other, but, mostly, she and Dad just cried together, leaving me yearning for the days when they fought because Alan had turned up somewhere he wasn't supposed to be.

Late in June, a man named Dan Hughes called me at my office. He said that he knew where Alan was and that he was safe. I had never heard of Hughes before, but the Houston Police Department had: someone on the homicide squad told me that he was the head of the black rackets and that I shouldn't worry; he wouldn't do anything to a white man. That night, I walked into his club on Southmore Street, in the ghetto. The music was loud. The jukebox had little dancing figures whirling around on a colorful neon screen. Looking for Hughes, I cut across the dance floor, through customers obviously puzzled by my sober white presence.

Hughes, a huge man wearing two gold watches with front teeth to match, told me to take a seat at the bar and then left me there for an hour, which I spent doing tequila shots. Finally, he returned and motioned for me to come into his office, a dank place with dim lighting and walnut walls.

"You can stop worrying," he said. "I got your brother sat down in Mexico."

"You're kidding. How do you know it's him?"

"Because he tole me so, baby. He tole me so."

"You've seen him?"

"Course I seen him. Why would I say I seen him if I hadn't?" Hughes leaned across his desk. "He run off with his chippy. He don't want to come back. But don't worry. Ole Dan'll bring him home. He won't have no choice."

Ole Dan told me to go back out to the bar and we'd talk business when his customers had left. I agreed, even though what he'd said was bullshit. I could believe that my brother might cheat on his wife but there wasn't any "chippy" and he wasn't in Mexico. But even propping up the bar at Dan's Club was better than sitting impotently back at my desk or in my apartment or in Harriet's house, longing for an unlabored breath. I was glad to be doing something, no matter how absurd, to find Alan. I was also a little drunk.

Before the last customers had left, I pushed open the door to Dan's office and walked in.

"What will it take to get my brother home?"

"Twenty-five thousand dollars. That reward ain't shit for what I'm doin'. "

"I want proof you actually have my brother."

"It don't work that way, baby. You put up the money. I bring him home."

"It don't work that way, Dan. You bring Alan home. Then you'll get your money."

I walked out and never heard from him again.

Then a former Imperial Carpet salesman told Dad that a nightclub singer he'd "been banging" knew something about Alan. Her name was Jenna Coy Huddleston, and my father persuaded him to phone her while Dad taped the call and listened in. Huddleston said that she'd heard a club owner say that Alan Berg had "gone off on a trip and wasn't coming back" because he'd told a gambler that the UH–UCLA game was fixed and the gambler lost $109,000. When Dad told the police, they said that Huddleston was a con artist who'd say anything for the reward. Sure enough, she called later the same day, demanding the $5,000 from Dad in exchange for information about Alan—unaware that he'd heard and taped what she had to say already. Dad slammed down the receiver.

So my father's reward had launched both of us into a world of hustlers and cons. Dad, especially, was defenseless, like a cancer victim running to Mexico to be cured with melon rinds, vulnerable to anyone who offered even the slightest clue, no matter how implausible, no matter the cost. An agonizing month passed before we finally got our first solid tip from a credible source. At the end of June, Dad hired Claude Harrelson, a private investigator and former Houston policeman with an excellent reputation among law enforcement agencies. Harrelson's uncle had been warden of the Lovelady unit of the Texas Department of Corrections, and his father was a guard there. Another uncle was a former FBI agent.

Not three days after being retained, Harrelson called Dad and asked to speak to him in private, away from both of their offices. They met at the Avalon Drug Store, where lots of oil deals were done. Dad found Harrelson sitting at a corner table. He seemed scared, my father told me, and warned Dad not to repeat what he was about to tell him to anyone, especially the authorities, because if word got out, Harrelson would be killed. Dad agreed.

Then Harrelson told my father that Alan had been murdered.

Dad felt at that moment that he might die. Everything was spinning: the walls and windows and Harrelson, too; he clutched the table to keep from falling to the floor. Dad finally asked him to repeat everything he'd said so he could decide what to do next, and when he still couldn't concentrate, told Harrelson that he was going to call his personal lawyer to come help him discuss the next steps. Harrelson said he'd walk out but Dad convinced him that the lawyer, Jim Cowan, had to keep the matter confidential—and the investigator agreed to stay. Then, with the three of them seated around the table, Harrelson said that for $3,000 his sources could turn up Alan's body. Dad said that made no sense; the reward he posted was already $5,000. Harrelson said he didn't understand it either but that was his sources' demand. Dad and Cowan left the Avalon and drove straight to Fannin Bank, where his loan officer listened to the story and advanced him $3,000 on Dad's promise to pay him back immediately out of the California CD. Then Dad wrote a check to Cowan, who was to endorse it over to Harrelson once Alan's body was found.

Dad drove home to wait for Harrelson's call. Harriet, Dayle, and I waited with him and Dot in their den, but hours went by and the phone didn't ring. Around midnight, my father covered his head with his hands and said, over and over, "I want my boy back. What have they done to my boy?" Then he left the room, sobbing and apologizing.

I followed him into his bedroom and sat down next to him on the bed.

"What more can I do?" he said. "I put out thousands of dollars. I've hired half a dozen investigators and nothing happens. The cops don't do anything."

I reassured my father that he had done all he could and that if we kept looking, we might still find Alan alive.

"You don't really believe that, do you, kid?" He put his arm around my shoulder and said, "You know, I do love you."

"Do you think it's too late for me to go to medical school?"

"Never."

At three in the morning, long after Harriet and Dayle and I had left, Dad's phone rang. The caller's voice was muffled. He said that the price was now $6,000. But it was a Saturday; the banks wouldn't be open, so Dad said he'd get the additional money first thing Monday morning. The phone went dead.

On Monday, at 6:00 a.m., he got another call, and the same muffled voice told him that the price was now $10,000. Dad assured whoever was on the phone that the money would be there. But in fact he'd had enough. That morning, with me listening in, Dad called Harrelson and told him that he was going to pick him up and that the two of them were going to the police. Harrelson refused. Dad pleaded with him but Harrelson insisted that going to the authorities would get him killed. Dad lobbed a volley of "goddamns" at him that did us both proud.

Then Dad and I went to the police, who listened politely as my father described what Harrelson had told him. The officers agreed that Harrelson was a believable source and that his tip probably did bear some truth, but if they ever questioned him, we never knew about it, and I don't believe they ever did.

So we were back to zero. Every day was excruciating. With each tip there followed interminable parsing of the informant's every word and inflection—but nothing ever turned up except more bribes and torment. One day at work, Dad got a call from another former salesman, telling him that Alan had been put through a meat grinder in a packing plant. Afterward, my sister sat by helplessly as he cried and vomited. Dad often phoned Alan's friends to pick their brains for something new, and no matter how seemingly insignificant the detail, he would follow up and obsess over it for days.

As tight-fisted as she was, Dot never said a word objecting to the money my father was spending on his search. But Dad looked elsewhere for warmth. For the first time in Linda's life, Dad leaned on her, calling her, hugging her, recalling funny stories about Alan and, many nights, stopping by her house to play with Linda's two-year-old daughter, who distracted Dad and calmed him down—for a few hours, anyway.

While it is said that everyone's suffering is unique, no one's could have exceeded Harriet's. With Alan gone, money was tight, and Harriet took a secretarial job at the county hospital. Sympathetic coworkers would show her unidentified corpses when they came in so she could see for herself whether it was her husband. "They bring in bodies that were found in the mud, facedown, filthy," she told me. "It's awful. It's never Alan." Nonetheless, she refused to burden her children, Lisa and Jonathan, now four and two, with her anguish. She told them repeatedly that their father loved them all very much—even the baby in her tummy—but he could not come home right now because he was off on a trip and she hoped he'd be back soon. While the adults around her dissected tips from Houston's underbelly, Lisa sat in the front yard and blew dandelions in the air. She said the "floaty" parts were her daddy and let them fall over her.

Dad fired Harrelson and hired another private investigator, this one recommended by one of Houston's most respected law firms. The investigator's name was Bob Leonard, and he always dressed like an FBI agent right out of the movies, in a gray suit and pretzel-thin tie. Almost immediately, Leonard discovered something valuable: he'd homed in on a possible murder site in Fort Bend County, just thirty minutes south of Houston. No one had found a body, but after talking to one of the officers who'd stumbled on the scene, and then visiting it himself, Leonard felt certain that a murder had been committed there.

Leonard convinced Dad that the only way to flush out what had happened in Fort Bend was to go to the papers.

The following Sunday, August 4, 1968, the Houston Post ran the first media report about Alan's disappearance, a front-page story with the headline:

Bloody Trail in Weeds: Was It Alan H. Berg's?

The article described how, on May 29, the morning after Alan disappeared, Fort Bend County deputy sheriff Roy Schmidt had pulled onto Levee Road at exactly 4:00 a.m. while listening to a weather report. He was performing a routine sweep for "car strippers," thieves who sold parts off cars they had stolen.

He saw car tracks on the freshly graded dirt road. He thought he saw a small white light blink. He drove a few yards down the road to an old dump, keeping his eyes on the tracks.

"The tracks were dug out," he said. "It looked like a car had got away in a hurry." The next morning, a ranch hand contacted the sheriff's office. He said he thought someone had slaughtered a calf on Levee Road. Schmidt drove back to the same spot, this time asking Deputy Ed Chesshire, his on-duty replacement, to meet him there.

There were signs of a fight beside the road, a pool of blood, and a bloody trail leading across the dump to a freshly dug hole near some trees. In a cow track near the dump were two or three cups of blood.

"I knew it wasn't a calf that was killed," said Schmidt. "No reason to bury a calf."

He searched the trail of blood—"enough blood for a man to bleed to death. Everybody laughed when I got down on my hands and knees and crawled down the trail. But I told them I was going to pick up something."

He did: a human hair, a Schaeffer pen like one Mom had given Alan, a broken hatchet handle, and a tuft of red carpet of a variety that Dad and Alan sold. The blood in the dirt was type A, which matched the "carpet executive" Alan Berg's, but there was no record of Alan's Rh factor—not even in the navy's files—that could prove definitively that the blood was his.

Dad and I were both interviewed for the article and I'm still appalled by what we said. I was quoted as saying that my brother was "a wild gambler, who gambles infrequently and badly." My father told the reporter that he thought Alan had been called into the FBI for questioning "about interstate gambling." From that point on, in the media, "carpet executive Alan Berg" became "gambler Alan Berg."

The article concluded almost like a eulogy:

Friends say his marriage is "the most successful thing about him." Perhaps, they add, he might even be considered over-protective. He had bought his children a swing set, but was afraid for them to play on it. He was afraid for his wife to drive at night.

He loaned money to everyone. The family has paid one $1,000 note he cosigned before he disappeared.

They have posted a $5,000 reward, which they hope will tempt someone who knows where he is. "Somebody here in Houston knows where that boy is—alive or dead," Nathan Berg says.

Alive. Even confronted with the Post article, my father tortured out scenarios that led to the possibility that "that boy" was alive. Leonard was right about using the media: the Post article forced the HPD into opening a missing-person file (seventy days after his disappearance) and even persuaded the fabled Texas Rangers to lend their statewide authority to the investigation.

Encouraged, Dad raised the reward to $10,000. And then, in the most unlikely development so far, a freshman congressman ramped up the search for my brother: George H. W. Bush.

Sol Rogers had arranged for Dad to meet with his local congressman, Beaumont's Jack Brooks, one of the most powerful men in Washington. But when Dad met with him in his DC offices, to try to convince the congressman to trigger an FBI investigation, Brooks discouraged him, saying it sounded like an essentially local matter, despite kidnapping being a federal offense. When Dad emerged from Brooks's office, disappointed and angry, he spotted Bush walking down the hall and pursued him. Bush welcomed Dad into his office, where my father once again laid out his reasons for getting the FBI involved. Bush listened carefully, then, making no promises, advised Dad to go home and reiterate what he'd said in a letter, which Dad wrote as soon as he got back.

My father had no right to expect Bush to do anything for him. Dad was a Yellow Dog Democrat who believed Republicans a species born without opposable thumbs. He didn't live in Bush's River Oaks district; in fact, he couldn't have lived there even if he could have afforded it, because Jews were excluded in the deed restrictions. Nonetheless, the same day he received Dad's letter, Bush forwarded it to J. Edgar Hoover along with a note of his own: "I would greatly appreciate your looking into this matter and advising me of your findings." One week later, on October 2, the FBI opened a file on Alan, citing as its jurisdiction the gambling case it was seeking to bring against Ted Lewin, with Alan as a potential witness—but mostly because Bush had insisted. The congressman then assigned his administrative aide to keep pressure on the FBI and to field Dad's calls when the congressman was unavailable. I don't know what Mr. Bush and my father said to each other, but their conversations comforted Dad like nothing else. I remember thinking that maybe the most compelling reason for George Herbert Walker Bush to spend so much time on the phone with Nathan Berg was, very simply, that—no matter how different the circumstances—Bush knew what it was like to lose a child. His first daughter, Robin, died of leukemia when she was only four years old.

With the FBI involved, field reports began flooding in. One of the earliest listed Alan's life insurance policies, each with double indemnity provisions that would pay Harriet a total of $80,000 if it turned out that Alan had been murdered. In addition, there was a $50,000 "key man" policy on both Alan and my father, a condition for obtaining Dad's small-business loan of the same amount—with the lender as the beneficiary to pay off the balance. Another report stated that my brother ran "a 'boiler shop operation' where high pressure telephone sales pitches were made by about 30 of his employees soliciting carpet business. Most of the customers are Negroes." The same report also stated something even we hadn't heard before: that Alan was a suspect in a bank robbery that had taken place a few days after his disappearance. In yet another report, an agent quoted a confidential informant as saying that Alan "dressed like a queer" (which might account for Mr. Hoover's personal interest in the case). But then the same informant had added, "Berg also did not run around on his wife and is quite a home-living [sic] individual who stayed home usually each day until about noon. The story that he was going to meet a girl at the time of his disappearance does not jibe with his pattern of normal behavior."

Normal behavior. For months we had lurched from one phony tip to another, rallying when one suggested that Alan was alive, plummeting when another said he was dead. And with each successive false lead we became even more anxious and uncoupled from any semblance of normal life.

Excerpted from RUN, BRO