22 Jul 2013 01:24:19

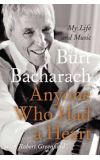

If only Burt Bacharach's life could be told exclusively through his compositions. It would be a soft-focus tale of tender heartache and innocent romance. But the songs were just Bacharach's trade, the lucrative business that won him Oscars, Grammys, the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song and a devoted generation of damp-eyed fans, including Cherie Blair and Laura Bush (the pair once serenaded him backstage in Dallas: "I thought that was wonderful").

The problem with Bacharach's life is the common one: the work edged out everything else, including wives, children and his longtime songwriting partner, Hal David. While the songs are lovelorn and honeyed, the reality is sometimes cruel, often painful. To be fair to Burt and his ghostwriter, Robert Greenfield, they haven't tried to skirt the truth. Spliced with Bacharach's stark recollections of bitter divorces and unseemly professional wrangling are the memories of those he met and married along the way. It means you get lines like this one, from his third wife, Carole Bayer Sager: "What I now realise is that nothing changes with Burt when he changes wives. The only thing that changes is the wife, but his routine remains the same." And this from his second, actress Angie Dickinson, after Burt had given her a list of 26 things that had to change in their marriage: "I don't remember Burt giving me an actual written list… If he had… I would have stuck pins in it and held it up to say, 'See what a prick I married?'"

Bacharach was obsessed: a lifelong insomniac kept awake by the music he heard in his head, a conductor who would make singers such as Dionne Warwick and Cilla Black do 30 takes of the same song before choosing the second. His ambition made him famous as a performer as much as a composer, but it also created an insatiable hunger – for bigger prizes, for winning (at horses as well as music), for sex. Bacharach was a prodigious shagger.

He's wonderfully blunt about his appetite. Bacharach recalls as a child reading Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises. "I really identified with the hero, Jake Barnes, who couldn't perform sexually because he was impotent. That was definitely not a problem for me." Indeed, no. Bacharach was constantly starting "little affairs" and remembers tender details like the high school girl with "colossal tits" who he would "dry-hump" and then "come just like that!" On tour in Russia with Marlene Dietrich he would wander the streets looking for girls who didn't have gold teeth. "By our third week… even the cows were starting to look good to me."

Of his long-suffering wives, Angie had the toughest ride. Their daughter, Nikki, was born more than three months early, weighing less than 2lb. As Bacharach has it: "If a child was born as prematurely as she was back then, there was no way she was going to come out with a full deck." Aged four, Nikki started collecting mounds of detritus – old batteries, dog poo, broken glass; at eight, Angie would buy Nikki pet mice and she'd kill them by throwing them against the wall. Soon enough, Bacharach left (sometime around that 26-point list). He remained involved in Nikki's life, and as her problems worsened, decided that the intensity of her relationship with Angie wasn't healthy and had his daughter committed to a clinic in Minnesota for 10 years. "Ten years!" writes Angie. "With no change because she didn't have the mechanism… That poor darling. She was so heroic and still loved the sonofabitch because Burt can charm everybody."

Nikki's story is the corrective to all the sugar-coated, west-coast glamour. Beneath the fanboy interjections from Mike Myers, Elvis Costello and Noel Gallagher ("If I could write a song half as good as … Anyone Who Had a Heart, I'd die a happy man") lies a layer of darkness. In her early 30s, Nikki – far too late diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome – started reading books about suicide. She spoke of killing herself but despite her threats, Bacharach never thought she'd do it. "But then suddenly she did." She left her father a note, which he's never read.

Bacharach ends the chapter about his daughter's death by quoting a song he wrote for her: "Nikki, it's you/ Nikki, where can you be?/ It's you, no one but you, for me/ I've been so lonely since you went away/ I won't spend a happy day/ Till you're back in my arms." And so another episode in this glittering, damaged life is translated into song, into emotion so meaninglessly simple that anyone can feel it.