04 Jun 2013 03:42:51

Not surprisingly, Theroux has not rushed back to Africa. Indeed, it has taken him a decade to arrange this return, in which he sets off to mirror his original journey with one that instead heads north from Cape Town up the continent's western edge. The purpose is to take a valedictory trip "to the violated Eden of our origins", he says, and to assess just what the 21st century has done to Africa, a land that the author has loved since he was a young peace corps teacher in Malawi.

Theroux's aim is to travel from South Africa to Timbuktu, via Angola, Gabon and Nigeria. It is a dream (his word) that is shattered long before he reaches his journey's halfway point. Three of the men he befriends en route are killed: one is bludgeoned to death by robbers, another is crushed by an elephant, while the last suffers a heart attack while swimming. His credit card is cloned in Namibia and he is defrauded of thousands of dollars. The filthy buses and cars in which he travels are invariably crammed with humans, chickens and goats and break down continually while being driven along disintegrating roads by drunks and maniacs.

With each mile he takes northwards, the poverty and corruption worsens and Theroux's spirits sink even further. Eventually he reaches Angola, a nation of immense mineral and oil wealth, which is run by a government that is simply "predatory, tyrannical, unjust, utterly uninterested in its people … and indifferent to their destitution and inhuman living conditions". The recent civil war that blighted the country for a decade has denuded it of all its wildlife, infrastructure and hope, Theroux discovers.

Thus the Africa described in The Last Train to Zona Verde turns out to be an even harsher, more miserable, more depressing place than the one depicted in its predecessor Dark Star Safari. There have been "few improvements, many degradations," the author notes. And in the end, it all proves too much.

As he is preparing to pass further north into the Congo, Theroux, the hardened doyen of travel writers, decides he can take no more and he turns tail to return to South Africa. "I had nothing to complain about – but the misery of Africa, the awful, poisoned, populous Africa; the Africa of cheated, despised, unaccommodated people, of seemingly unfixable blight: so hideous, really, it is unrecognisable as Africa at all. But it is of course – the new Africa."

It should be noted that Theroux is no longer the likely lad who once nipped around Europe, Asia and the Americas in his great travelogues The Great Railway Bazaar and The Old Patagonian Express. He is now in his 70s and has to carry pills for his gout and other ailments. "As I grow older, the consolations of home take on a deeper meaning," he admits.

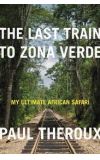

Stressing such frailties would be unjust, however. Time may have been hard on Theroux but it has been far, far crueller to Africa, a continent of burned-out villages, landmines, amputees, refugees and orphans, in the writer's eyes. It is an extraordinary, terrifying vision which, in other hands, might speedily wear down the reader. But Theroux's tight, angry prose propels you through the pages – although the book is not without the odd flaw. Its title and cover clearly suggest this is a train travelogue – a Theroux speciality, after all. In fact, it contains only three paragraphs about his trip's single, brief rail journey. I mention this lest the casual bookshop browser believes this book will recount the tale of a fun trip on African trains. It doesn't. In addition, the author's antipathy to aid agencies – which he blames for nearly all of Africa's woes – is crudely overstated, in my view.

These are minor points, however. The Last Train to Zona Verde is a riveting, chilling read, one that outlines a reality that sometimes seems more like the apocalyptic fiction of writers such as Cormac McCarthy. Certainly, Theroux notes that the horrors now unravelling in Africa – dwindling resources, enveloping slums, spreading starvation and slaughtered wildlife – are happening on other continents, albeit with greater subtlety. Old Africa hands may quibble with Theroux's sweeping dismissal of the continent's prospects. But as a wake-up call (and possibly the author's travel-writing swansong), The Last Train to Zone Verde is an uncompromising, unsettling work.