25 Nov 2012 01:55:58

It was extraordinary, what Ireland's economic boom did to the way people talked about land. Granted, Irish thinking on that matter was hardly in a healthy state to begin with, but by the mid-2000s, if a piece of land was not a site, it was seen by many as a wasted opportunity. At a striking moment in her new memoir – ostensibly the story of a family inheritance, but also the story of a country at a deranged moment in its history – Selina Guinness hears, on her car radio, a property developer bemoan the "derelict fields" on Dublin's outskirts. This is 2006; for land so close to the city to remain zoned for agriculture is, the developer suggests, shameful.

Guinness, as she listens, is headed home to her own Dublin fields: Tibradden, the house and 120-acre farm of which she and her husband, both academics, have recently found themselves in charge. The new responsibility has given Guinness an intimate understanding of land: meadows are no longer "background wash or colour" but something much more substantive – crops, pasture, soil. And so, though the developers literally circle the skies above Tibradden, and estate agents declare its "hope value" to be "almost beyond measure", Guinness is determined to stand her ground. "Sweat," she writes, reflecting on the generations of work that have gone into the place, "creates an attachment beyond talk of property and prices."

So does stout, some might murmur, noting the author's surname – but no Guinness fortune supports Tibradden. The author's wing of that family long ago forsook brewing wealth for holy orders, and the ancestral estate was in fact married into, in 1859. It is by now an oddity, a Victorian house and a working farm tucked down a lane in Dublin's southside suburbs. Guinness spent her teenage years here in the care of her uncle and grandmother. In 2004, this time joined by her husband, she is once again living with her uncle when he becomes ill and dies.

The existence of a discretionary trust means that her inheritance is not immediate; she must nevertheless act immediately to keep the farm from collapse. But then the EU's common agricultural policy comes into full effect, and Tibradden's farming practices are about as aligned to its schemes, and to the rural environment protection scheme (Reps), as the old house – with its Bakelite phone and its ceramic fuses – is to the internet age. Her uncle, who shut off all disordered rooms, also shut out disordered situations; Guinness now faces the consequences of his well-meaning denial, especially when it comes to the farm's elderly stewards, Joe and Susie Kirwan, who inhabit its gate lodge with their disabled son. As the estate agents trumpet their insidious notion of "hope value", Guinness must negotiate the altogether more difficult business of actual hopes and fears; how they clash, how they fester.

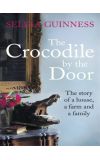

The Crocodile by the Door, shortlisted for the 2012 Costa biography award, is an appealing book for several reasons. It is a surprisingly entertaining primer on the travails of farming today, from ungovernable sheep to unfathomable bureaucracy; a fascinating glimpse of what had become of the Anglo-Irish by the late 20th century and into the 21st; an elegant modern pastoral and, at the same time, an astute dismantling of that genre; and a meditation on the meaning of labour, and on how hard work shapes identity as well as achievement.

Guinness has a poet's eye for detail, from the beautiful to the banal: a torch "spills a bowlful of light", a Hoover "lies next to the sofa like a dejected dog". Her relationship with her uncle is drawn in all its shades of complicated love, as is her narrative of new marriage and new motherhood. And she vividly evokes Tibradden's archaeology through the women who have lived and worked there over the centuries, down to proud, strong-minded Susie Kirwan, who ruffled feathers by inheriting the farm's stewardship in the 1950s, when she was around Guinness's age.

The changes Guinness must now make are necessary not just for the survival of the farm, but for the protection of the Kirwans, who have long lived in a kind of furtive squalor. Guinness is discomfited to find that she cannot address this situation without looking, to the Kirwans and to others in the locality, like a harsh landlord of the ascendancy class to which she, however distantly, belongs – class divisions cannot be chatted away.