22 Sep 2010 00:39:58

The Swede played him most memorably, followed by the portly middle-aged white guy from Missouri. When they were both done and the series was gasping its final breaths, the one-time radio announcer for the Boston Red Sox got a short-lived shot.

But throughout his phenomenally successful 17-year run in Hollywood movies — from the Depression's beginnings well into postwar America — never, ever was Charlie Chan brought to life by a Chinese actor.

Unsurprising. Because from his earliest appearances in books and movies, the ethnically Chinese detective from Hawaii invented by Earl Derr Biggers was, really, always about racial politics in one way or another. Yet he was never quite what you'd expect.

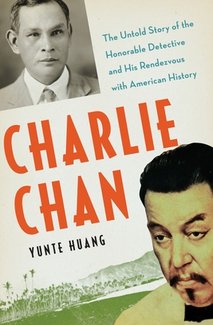

It is this continual defying of expectation that breathes life into Yunte Huang's new book, "Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous With American History," an attempt to trace the character to its origins and link it up with a real-life Honolulu police officer named Chang Apana.

Why do this at all? Huang, a China-born English professor at the University of California, sums it up: "To write about Charlie Chan is to write about the undulations of the American cultural experience."

Huang is an elegant and amiable, if occasionally overly hopeful, tour guide. It is fascinating to travel with him as he unearths the layers of racial significance surrounding the character's "tortured legacy in American culture."

While many Asians dismiss Charlie Chan as pure racism — according to Huang, the National Asian American Telecommunications Association calls the detective "one of the most offensive Asian caricatures of America's cinematic past" — Huang finds more to the story.

First, he journeys to Hawaii to compile a semi-biography of Apana, a bullwhip-wielding Honolulu cop who resisted corruption, patrolled diligently for decades and, in an environment rife with racism, made detective and became legendary.

In the 1920s, Apana's reputation drew the attention of Biggers, who was researching a new novel that would, ultimately, give birth to Charlie Chan. While Huang proves his case only partially in connecting Apana with Chan's origins, he does show how both Biggers and Warner Oland — the Swedish actor who played Chan — perceived Apana as the cinematic character and met with Apana in Hawaii.

"If Charlie Chan must have an original, he could not have a better one," Huang quotes Biggers as saying, though the evidence he presents suggests that Biggers may have retrofitted the origin story to make Apana the inspiration.

Charlie Chan had a brief life in silent movies in the late 1920s, when he was portrayed by at least two Asian actors. The character really took off, however, when Oland assumed the role in 1931, launching a series that would traverse nearly two decades and two movie studios.

Asians, and Chinese in particular, have often had an uneasy history in American cinema. But to dismiss Chan's two main portrayers, Oland and Sidney Toler, as the Pacific Rim equivalents of Al Jolson in blackface would be ignoring part of the story.

Watching the films today, from the vantage point of someone who has spent large chunks of time in China, the effect is startlingly (though not always) inoffensive. Both Oland and Toler, pidgin though their English lines can be, infuse Chan with a gravitas and dignity that at times overshadows the stereotyping.

More obviously disturbing is the way the talented 1940s character actor Mantan Moreland was cast as Chan's jumpy, pop-eyed chauffeur, offering comic relief in a Stepin Fetchit shuckin' and jivin' style.

Yet offensiveness can be a product of its era.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the presence of a positive Chinese authority figure was a big draw for Asian audiences accustomed to sinister Fu Manchu movies and comic books, and broad stereotypes of Chinese as big-toothed, slant-eyed buffoons. No matter that the actors themselves weren't Asian; at least the Chan offspring — Sons No. 1, 2 and 3, played by Keye Luke, Victor Sen Yung and Benson Fong respectively — were.

And the notion of all of them circulating openly in white society, with little obvious racism aimed at them, was progressive for films of the time. What's more, the addition of Moreland to the cast in the 1940s was a drawing card for black audiences. So it can be difficult to tell who found what offensive when.

(Stereotyping, of course, goes both ways: In 1980, one of the first American films shown in China after relations resumed was a nasty evil-sheriff potboiler called "Nightmare in Badham County," which chronicles some of the worst excesses of the American South. Given the Chinese government's intense message management during that period, the decision to exhibit that movie was probably not coincidence.)

Asian stereotypes are hardly gone in today's America; they endure, albeit in different ways: the high-schooler who is really good at math and has no social life because he or she is so driven to excel; the young women who serve as eye candy for white guys with "yellow fever."

One difference, though, is that these days it's sometimes Asians themselves who push the racial envelope with some irony-laced wink-nudge. Consider the Asian-owned Xiaoye, a new restaurant in New York with menu items that poke fun at the culture — including "Concubine Cucumbers" and the "Everything but the Dog Meat Platter."

"Sometimes late at night, I turn on the TV and a Chinaman falls out," Huang writes, aware that he is using a term laden with derisive heritage. He has great affection for Charlie Chan: He understands the anger that the stereotype has produced, but finds a subtlety that so many do not see.

Charlie Chan was a stereotype, yes, born from the mind of someone who knew little about Asians and amplified by moviemakers who probably knew even less. Today, with our knowledge of China far more nuanced than a few generations ago, we can cackle or bristle at Warner Oland or Sidney Toler parading around in a white suit spouting fortune-cookie wisdom.

Yet when those movies were filmed, Huang argues persuasively, Charlie Chan represented a beginning — a smart, positive harbinger of racial possibility in an era that had little. It took a while to gain traction, true. But sometimes, the journey of a thousand miles actually does begin with a single step.

But throughout his phenomenally successful 17-year run in Hollywood movies — from the Depression's beginnings well into postwar America — never, ever was Charlie Chan brought to life by a Chinese actor.

Unsurprising. Because from his earliest appearances in books and movies, the ethnically Chinese detective from Hawaii invented by Earl Derr Biggers was, really, always about racial politics in one way or another. Yet he was never quite what you'd expect.

It is this continual defying of expectation that breathes life into Yunte Huang's new book, "Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous With American History," an attempt to trace the character to its origins and link it up with a real-life Honolulu police officer named Chang Apana.

Why do this at all? Huang, a China-born English professor at the University of California, sums it up: "To write about Charlie Chan is to write about the undulations of the American cultural experience."

Huang is an elegant and amiable, if occasionally overly hopeful, tour guide. It is fascinating to travel with him as he unearths the layers of racial significance surrounding the character's "tortured legacy in American culture."

While many Asians dismiss Charlie Chan as pure racism — according to Huang, the National Asian American Telecommunications Association calls the detective "one of the most offensive Asian caricatures of America's cinematic past" — Huang finds more to the story.

First, he journeys to Hawaii to compile a semi-biography of Apana, a bullwhip-wielding Honolulu cop who resisted corruption, patrolled diligently for decades and, in an environment rife with racism, made detective and became legendary.

In the 1920s, Apana's reputation drew the attention of Biggers, who was researching a new novel that would, ultimately, give birth to Charlie Chan. While Huang proves his case only partially in connecting Apana with Chan's origins, he does show how both Biggers and Warner Oland — the Swedish actor who played Chan — perceived Apana as the cinematic character and met with Apana in Hawaii.

"If Charlie Chan must have an original, he could not have a better one," Huang quotes Biggers as saying, though the evidence he presents suggests that Biggers may have retrofitted the origin story to make Apana the inspiration.

Charlie Chan had a brief life in silent movies in the late 1920s, when he was portrayed by at least two Asian actors. The character really took off, however, when Oland assumed the role in 1931, launching a series that would traverse nearly two decades and two movie studios.

Asians, and Chinese in particular, have often had an uneasy history in American cinema. But to dismiss Chan's two main portrayers, Oland and Sidney Toler, as the Pacific Rim equivalents of Al Jolson in blackface would be ignoring part of the story.

Watching the films today, from the vantage point of someone who has spent large chunks of time in China, the effect is startlingly (though not always) inoffensive. Both Oland and Toler, pidgin though their English lines can be, infuse Chan with a gravitas and dignity that at times overshadows the stereotyping.

More obviously disturbing is the way the talented 1940s character actor Mantan Moreland was cast as Chan's jumpy, pop-eyed chauffeur, offering comic relief in a Stepin Fetchit shuckin' and jivin' style.

Yet offensiveness can be a product of its era.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the presence of a positive Chinese authority figure was a big draw for Asian audiences accustomed to sinister Fu Manchu movies and comic books, and broad stereotypes of Chinese as big-toothed, slant-eyed buffoons. No matter that the actors themselves weren't Asian; at least the Chan offspring — Sons No. 1, 2 and 3, played by Keye Luke, Victor Sen Yung and Benson Fong respectively — were.

And the notion of all of them circulating openly in white society, with little obvious racism aimed at them, was progressive for films of the time. What's more, the addition of Moreland to the cast in the 1940s was a drawing card for black audiences. So it can be difficult to tell who found what offensive when.

(Stereotyping, of course, goes both ways: In 1980, one of the first American films shown in China after relations resumed was a nasty evil-sheriff potboiler called "Nightmare in Badham County," which chronicles some of the worst excesses of the American South. Given the Chinese government's intense message management during that period, the decision to exhibit that movie was probably not coincidence.)

Asian stereotypes are hardly gone in today's America; they endure, albeit in different ways: the high-schooler who is really good at math and has no social life because he or she is so driven to excel; the young women who serve as eye candy for white guys with "yellow fever."

One difference, though, is that these days it's sometimes Asians themselves who push the racial envelope with some irony-laced wink-nudge. Consider the Asian-owned Xiaoye, a new restaurant in New York with menu items that poke fun at the culture — including "Concubine Cucumbers" and the "Everything but the Dog Meat Platter."

"Sometimes late at night, I turn on the TV and a Chinaman falls out," Huang writes, aware that he is using a term laden with derisive heritage. He has great affection for Charlie Chan: He understands the anger that the stereotype has produced, but finds a subtlety that so many do not see.

Charlie Chan was a stereotype, yes, born from the mind of someone who knew little about Asians and amplified by moviemakers who probably knew even less. Today, with our knowledge of China far more nuanced than a few generations ago, we can cackle or bristle at Warner Oland or Sidney Toler parading around in a white suit spouting fortune-cookie wisdom.

Yet when those movies were filmed, Huang argues persuasively, Charlie Chan represented a beginning — a smart, positive harbinger of racial possibility in an era that had little. It took a while to gain traction, true. But sometimes, the journey of a thousand miles actually does begin with a single step.